Ancient Chinese Musical Numerology

How Do the Luo River Diagram and the Twelve Earthly Branches and Twelve Musical Modes Achieve Harmonious Unions?

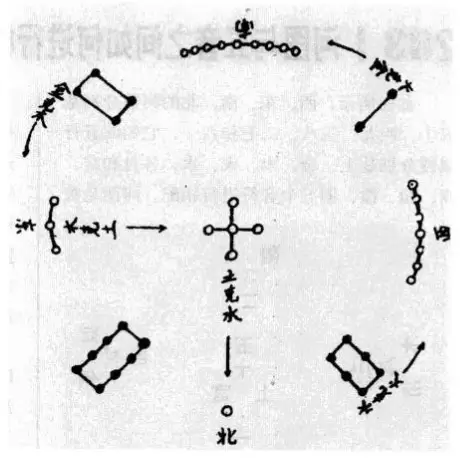

Within the Luo River Diagram, the twelve branches and the twelve musical modes are arranged into six groups. The “Zhou Li” records: “When playing Tai Cu, sing Ying Zhong.” Here, Tai Cu corresponds to the Yin hour and Ying Zhong to the Hai hour; when these two unite, they mirror the union of numbers seven and four in the Luo Diagram, resulting in eleven. Similarly, “When playing Gu Xi, sing Nan Lü” pairs Gu Xi with Chen and Nan Lü with You, their combination corresponding to the merging of numbers five and six, again totaling eleven. In the case of “Wu She and Jia Zhong,” Wu She stands for Xu while Jia Zhong represents Mao, their union likewise matching the numbers five and six to yield eleven. The pairing “Rui Bin and Han Zhong” equates to Wu and Wei, corresponding to the union of numbers three and eight, thus producing eleven. Finally, “Yi Ze and Xiao Lü” aligns Yi Ze with Shen and Xiao Lü with Yi; these two represent the combination of numbers ten and one. Although the Luo Diagram does not contain a ten, the numbers four and nine are connected in such a way that they resemble ten and nine, which permits the substitution of four for ten.

How Are the Hetu Diagram and the Five Musical Notes Correlated?

The numerical values of the Hetu associated with the West, East, South, and North are fifty, forty-nine, thirty-eight, twenty-seven, and sixty-one respectively. Their corresponding five-element properties are earth, metal, wood, fire, and water, each matched with one of the musical notes: Gong, Shang, Jue, and Yu. The Hetu is the origin of numbers, and the musical scale is likewise derived from it. As described in the “Yue Ling,” spring, associated with wood, represents the Jue note and corresponds to the number eight; summer, governed by fire, represents the Zhi note and corresponds to the number seven; the center, associated with earth, represents the Gong note and corresponds to the number five; autumn, linked with metal, represents the Shang note and corresponds to the number nine; winter, associated with water, represents the Yu note and corresponds to the number six. The four musical notes assigned to the four directions hence reflect their numerical relationships—four corresponds to Shang, three to Jue, two to Zhi, and one to Yu. Qingjiang Yong, in his “He Luo Jing Yun,” asserts: “Since the five tones already possess an order of magnitude as well as positions in the five directions, they inherently manifest an order of mutual generation.” From top to bottom, the tones arrange themselves in a descending sequence that conforms to the generative order of the five elements. The five resultant numbers symbolize the five “muddy” tones, encompassing the entirety of the musical scale, while the five originating numbers represent the five “pure” tones, which comprise half of the scale. The principal tone, Gong, occupies the center and corresponds to the number five.

What Is the Relationship Between the Transformation Laws of the Hetu and the Five Musical Tones?

The variability inherent in the five musical tones within the Hetu is engendered by the union of two numbers. When five and ten combine, they form fifteen, which still reflects a five-digit number; thus, the position of the earth element’s Gong tone remains unchanged. In the southern direction, the combination of two and seven produces nine; subtracting five yields four, so the Zhi note originally associated with the fire position transforms into the Shang note corresponding to the metal position. In the western sector, the combination of four and nine gives the number thirteen; after subtracting ten to obtain three and then subtracting five to reach eight, the Shang note of the metal position is transformed into the Jue note associated with the wood position. In the northern direction, one and six unite to form seven; subtracting five yields two, so the Yu note of the water position converts into the Zhi note of the fire position. Finally, in the eastern sector, three and eight combine to yield eleven; subtracting ten results in one, and subtracting five results in six, so the Jue note originally linked to the wood position shifts to become the Yu note of the water position.

The “Shi Ji · Lü Shu” records: “Shang, nine; Yu, seven; Jue, six; Gong, five; Zhi, nine.” Here, “Shang, nine” indicates that the Gong tone in the fifth position gives rise to the Zhi tone in the ninth position. The principles governing the five tones can thus be deduced from the numbers within the Hetu. The ordered sequence of the five tones forms the core of vocal music and musical theory. The Gong tone at a certain numerical position generates the Zhi tone at a higher position; similarly, the Shang tone at the eighth position gives rise to the Yu tone at the seventh position, the Jue tone at the sixth position begets the Gong tone at the fifth, the Wei tone at the fourth produces the Shang tone at the third, and the Yu tone at the second gives rise to the Jue tone at the first. The arrangement whereby the Zhi and Yu tones precede the Gong tone, and the Shang and Jue tones follow it, underscores the significance of the Hetu in elucidating the rules of sound and musical harmony. In essence, the principles of acoustics and musical theory can be entirely derived from the Hetu—a remarkable invention of ancient Chinese scholars.

In modern times, the principles of balance and harmony derived from these ancient Chinese philosophical systems have inspired various art forms and design concepts. Yin yang jewelry, for instance”could” be seen as a creative manifestation of the harmony between opposing forces, much like how the Hetu and Luo Diagrams illustrate the interconnectedness of different elements and principles in achieving equilibrium.