Chinese Traditional Homes & Architecture

History of Architecture: An Overview of Traditional Chinese Residences

The origins of Chinese residential architecture can be traced back to prehistoric times. Early settlements were characterized by communal living and a collective way of life, which profoundly influenced the evolution of domestic dwellings. Beyond mere habitability, these structures were designed to evoke auspiciousness and stability; aspects such as site selection and orientation were carefully governed by feng shui principles.

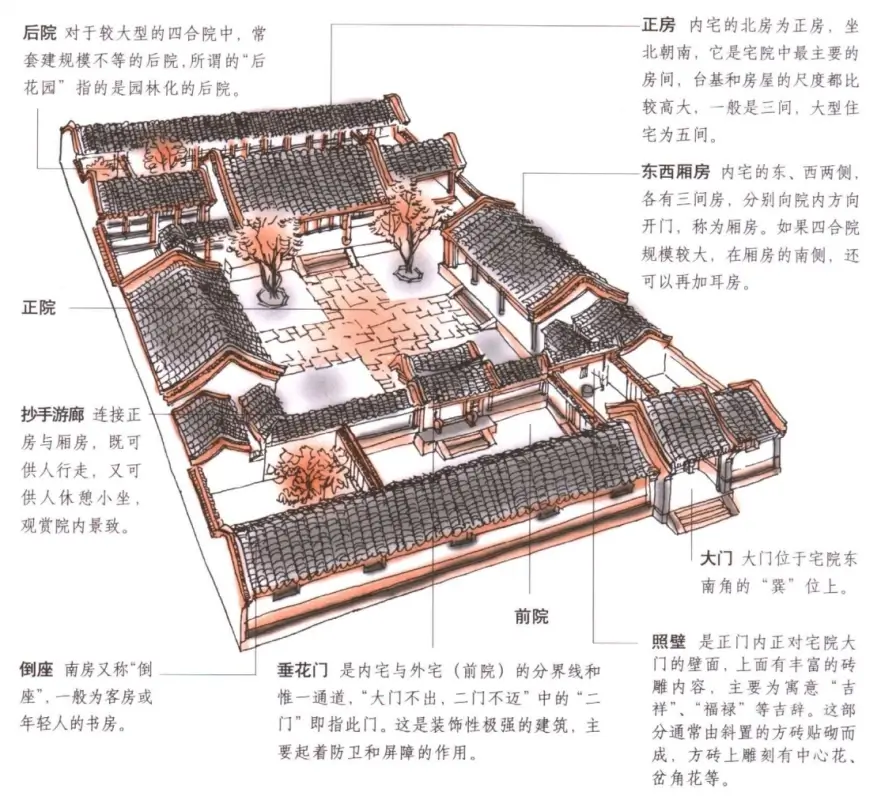

Northern Courtyard Houses: The Quintessential Siheyuan

In northern China, the archetype is the Beijing siheyuan—a traditional courtyard residence distinguished by its symmetrical, enclosed exterior and expansive, open interior. Multiple courtyards at the heart of the compound underscore the strict separation between public and private realms and reflect the hierarchical, clan-based social order. The robust yet understated design exudes a sense of dignified simplicity. Notably, the main entrance is typically positioned at the southeastern corner; each door serves as a symbolic threshold, marking the gradual deepening of a visitor’s intimacy with the household.

- Main Hall (正房): The principal room of the inner compound, usually located at the northern end and oriented to face south. Characterized by an elevated platform and generous proportions, a standard residence typically comprises three such rooms, while larger estates may include five.

- East and West Wings (东西厢房): Flanking the inner residence are three-room structures on either side that open onto the courtyards. In expansive siheyuan, additional annexes known as “ear rooms” (耳房) may be appended to the southern side.

- Main Entrance (大门): Strategically set in the “Xun” position at the southeast corner of the compound.

- Screen Wall (照壁): Located directly behind the main door, this wall is lavishly adorned with intricate brick carvings that invoke symbols of good fortune and prosperity. Constructed with slanted square bricks, it often features central floral motifs and angular decorative patterns.

- Hanging Floral Door (垂花门): Serving as the sole passage and boundary between the inner and outer compounds (the front courtyard), this ornately decorative door functions as both a defensive barrier and a symbolic partition, encapsulating the adage, “one does not step out of the main gate nor cross the secondary gate” without due consideration.

- Inverted Seat (倒座): Also known as the “southern room,” this space typically functions as a guest chamber or a study for younger family members.

- Covered Walkway (抄手游廊): This corridor connects the main hall to the wing rooms, offering a shaded passageway for both leisurely strolls and brief repose while admiring the courtyard’s vistas.

- Rear Courtyard (后院): In larger siheyuan, additional rear courtyards—often landscaped into what might be termed “back gardens”—are incorporated to enhance the spatial composition of the residence.

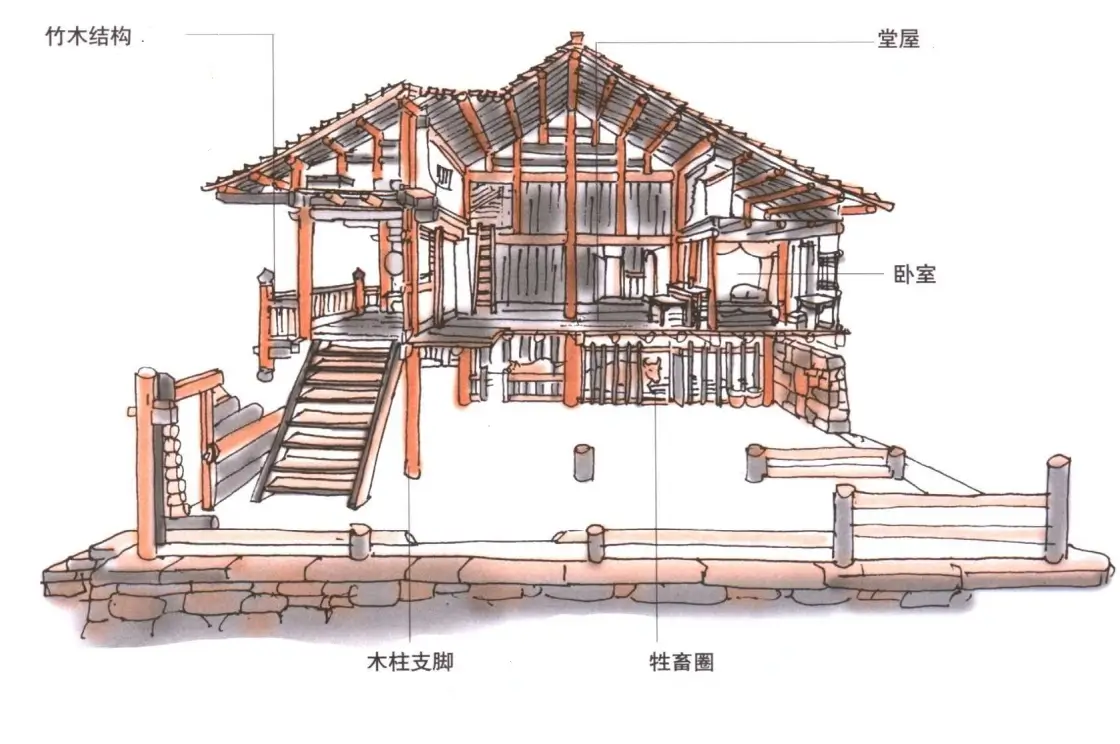

Stilt Houses (干栏式民居)

Commonly referred to as “diaojiaolou,” stilt houses feature an elevated lower level—traditionally used for housing livestock and storage—while the upper level accommodates a front porch with a sunning terrace and, at the rear, the main hall and private quarters. Access between the two levels is provided by an internal staircase. Predominantly constructed of timber, these buildings utilize wooden boards not only for beams and columns but even for the walls themselves. This distinctive form is widespread in southern regions such as Guangxi, Yunnan, Guizhou, the Sichuan–Chongqing area, Hubei, Hunan, and on Hainan Island.

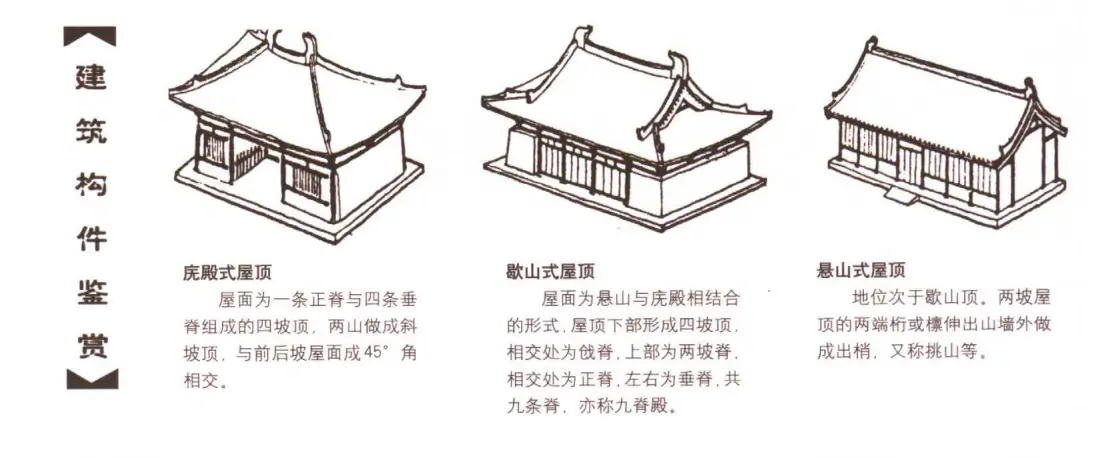

Roof Styles

- Pavilion Roof (庑殿式屋顶): This style features a four-sloping roof composed of a prominent main ridge flanked by four subordinate eaves ridges. The gable ends form sloping surfaces that intersect with the front and rear roofs at a 45° angle, lending the structure a stately appearance.

- Hip-and-Gable Roof (歇山式屋顶): Combining elements of the suspended mountain and pavilion styles, the lower portion of the roof forms a four-sloping structure where the intersecting hips define the rafter lines, while the upper section culminates in a central main ridge. Flanked by additional eaves on both sides, the roof displays a total of nine distinct ridges, earning it the appellation “Nine-Ridge Pavilion.”

- Suspended Mountain Roof (悬山式屋顶): Slightly subordinate to the hip-and-gable style, this roof features beams or purlins that extend beyond the gable walls to form projecting eaves, commonly referred to as “挑山.”

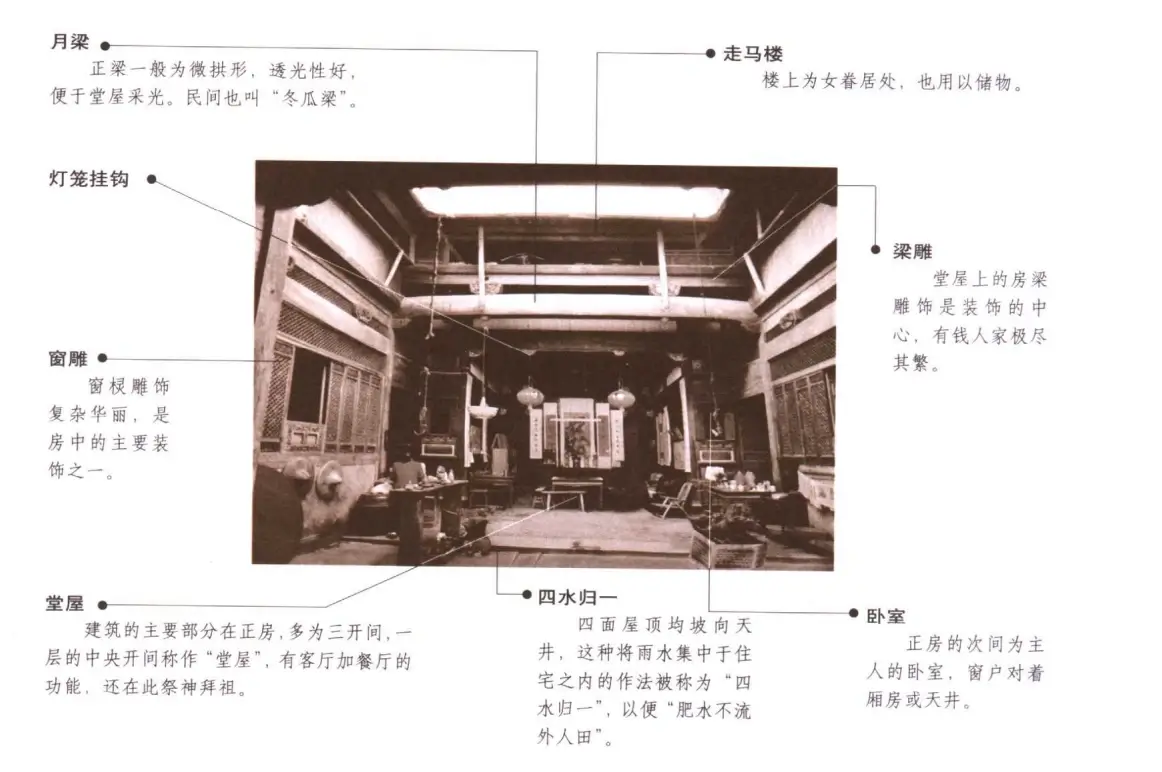

Southern Courtyard Houses with Central Atria

Often evolved from the traditional siheyuan, southern courtyard houses are typically configured as interconnected structures encircling a small central atrium or “tianjing.” In regions where winters are bitter, summers swelter, and the rainy season is prolonged—coupled with high population density—these houses are frequently built over two to three stories. The narrow central atrium is a critical design element, facilitating both ventilation and thermal regulation. Affluent families often extend these compounds laterally and longitudinally to form extensive, integrated courtyards. This architectural typology is prevalent in southern Anhui, as well as in Wuyuan and the central and northern parts of Jiangxi Province.

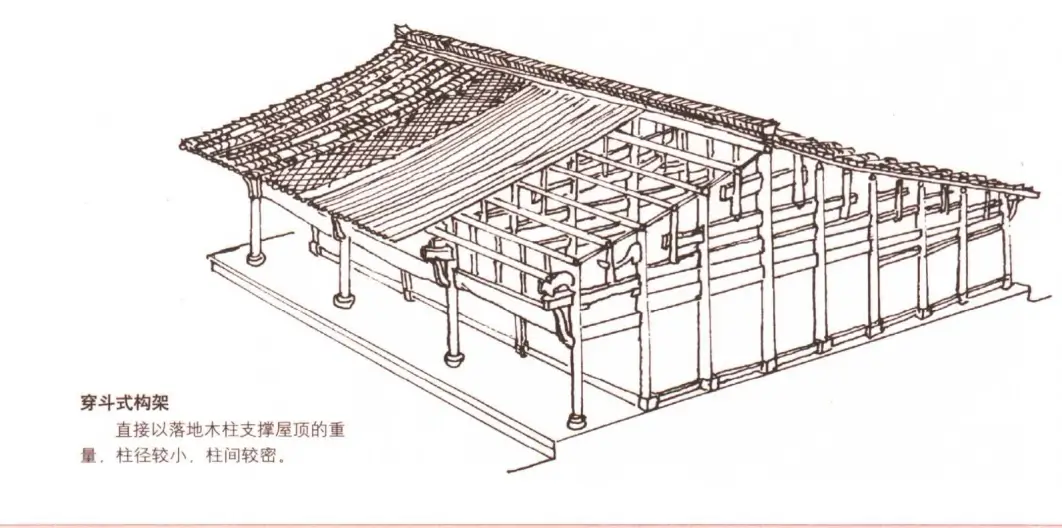

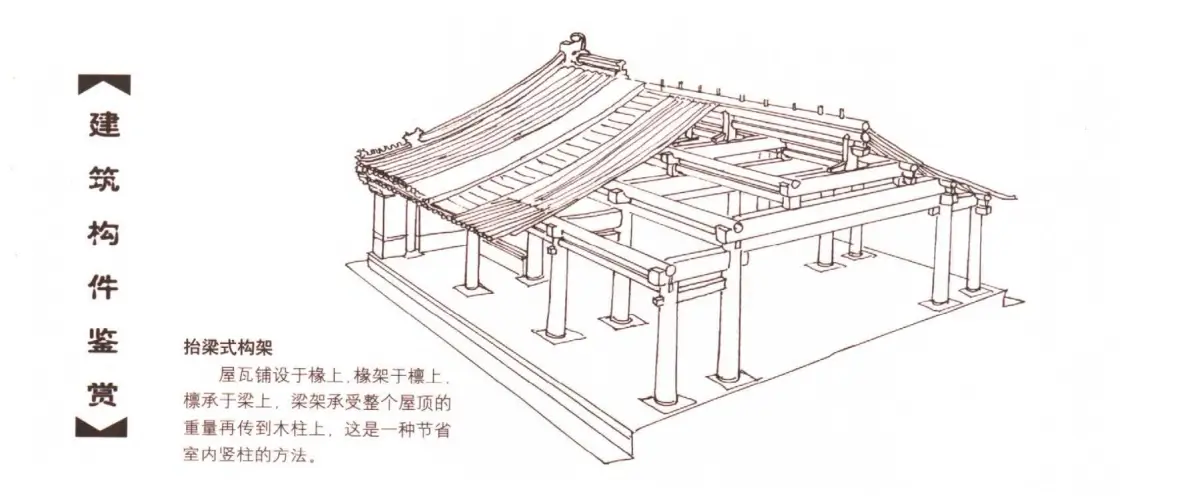

Raised Beam Construction

In this ingenious method, roof tiles are laid upon purlins, which themselves rest on beams that bear the entire weight of the roof. This load is then transferred to the wooden columns, thereby minimizing the need for additional vertical supports within the interior space.

Northwestern Cave Dwellings

An estimated 40 million people in China reside in various forms of cave dwellings, with those in northwestern Shaanxi being the most exemplary. These include stone-built caves, brick-built structures, and earthen dwellings excavated from cliff faces—once outfitted with doors and windows, these are known as earthen caves. One variant is carved parallel to the edge of a loess cliff, resulting in several isolated cave cells; another is excavated from level ground, initially forming a vast, square, flat-bottomed well from which individual cave chambers extend inward, permitting passage for both pedestrians and livestock.