Exploring the Philosophy and Wisdom of the I Ching

Ze Cheng believes that, as a Chinese person, even though many might not fully grasp the I Ching, it is nearly impossible not to be intrigued by it. The I Ching seems imbued with forces that transcend ordinary human comprehension. Driven by an insatiable curiosity, I began my study of the I Ching at the age of twenty‐five precisely because of its profound mystery and captivating allure—the more impenetrable it appeared, the more I yearned to understand it.

I am convinced that many people study the I Ching; however, most are really focused on its divinatory techniques—such as BaZi (Four Pillars of Destiny), physiognomy, Liu Yao (six-lines divination), Feng Shui, Qimen Dunjia, and the like. Yet, you may notice an inherent flaw in these methods: when presented with the identical hexagram, the same line inscription, or the same BaZi chart, different practitioners can offer divergent interpretations. The discrepancies between these interpretations may sometimes be as slight as 5% to 20%—especially in BaZi—illustrating how even the smallest error can lead to vastly different outcomes.

In my early days of study, I sought to glean insights into my own destiny—periodically consulting my BaZi chart and using coin tosses for Liu Yao divination. However, on November 17, 2024, at around 9 a.m., my father passed away unexpectedly. In October, I had consulted two fortune-tellers about my fate, yet none of them, through my BaZi, foresaw this tragic event. That experience rendered the notion of predicting one’s destiny via BaZi utterly absurd to me.

Thus, this article is not intended as a guide to peering into your fate through the divinatory aspects of the I Ching—nor do I possess the expertise to instruct you in techniques like Zi Wei Dou Shu or complex BaZi charting. Moreover, I contend that attempting to divine one’s destiny is ultimately meaningless; you are the director of your own life’s film. Instead, this article aims to explore the underlying principles of the I Ching—its philosophical, methodological, and psychological dimensions.

To truly appreciate the I Ching, one must consider four seminal figures: Fuxi, King Wen of Zhou, the Duke of Zhou, and Confucius.

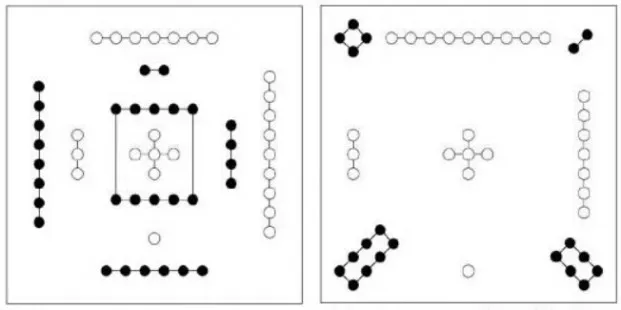

Legend has it that during the time of Fuxi, a celestial dragon-horse emerged from the Yellow River. The spiraling hairs on its body transformed into a diagram described as “1 and 6 at the bottom, 2 and 7 at the top, 3 and 8 to the left, 4 and 9 to the right, and 5 and 0 in the center”—the so-called “Hetu.” Fuxi employed the Hetu as the blueprint for creating the Eight Trigrams. Initially, these trigrams were devised solely for weather forecasting. Fuxi assigned the eight trigrams—Qian (☰), Kan (☵), Gen (☶), Zhen (☳), Xun (☴), Li (☲), Kun (☷), and Dui (☱)—to correspond respectively with the elements of Heaven, Water, Mountain, Thunder, Wind, Fire, Earth, and Lake. By observing changes in the heavens, the earth, and seasonal phenomena, Fuxi used these symbols to predict the weather and thereby guide agricultural production.

King Wen of Zhou (Ji Chang), the chieftain of the Zhou tribe at the end of the Shang dynasty, composed the “Zhou Yi” while in captivity. It is worth noting that the Shang dynasty was notorious for its practice of human sacrifice to appease the heavens—offering what they regarded as vital life forces, portions of which were even distributed among their subordinates. According to lore, King Zhou of Shang, impressed by the exemplary governance of King Wen’s tribe, recognized his talent and sought to sacrifice him to the Shang deities. Yet, King Wen’s son, Bo Yikao, intervened by sacrificing himself; after his sacrifice, his flesh was apportioned to King Wen. This account—distinct from the deliberately demeaning portrayals in later mythologies such as the Investiture of the Gods—suggests that King Zhou considered Ji Chang exceptionally important, as if bestowing upon him the honor of partaking in the sacred offerings. Consequently, some have speculated that the “Zhou Yi” is essentially a treatise on military strategy, its true purpose obscured by the evolution from the Eight Trigrams to 64 hexagrams designed for formulating battle tactics. Of course, this remains mere conjecture.

The third pivotal figure is the Duke of Zhou (Ji Dan), the fourth son of King Wen and the brother of King Wu (Ji Fa). It is attributed to him that the line inscriptions (yao ci) were composed—or, as some suggest, he refined, revised, and augmented the original texts of the 64 hexagrams so as to better align with the society and era of his time. Since each hexagram consists of six lines, his contributions amount to a total of 384 line statements.

Lastly, Confucius contributed the “Xici” to the I Ching—also known as the “Ten Wings”—which serve as a commentary on the classic text. In later generations, the original I Ching text and Confucius’s commentaries were merged into a single work known as the “Zhou Yi.” Alternatively, one might say that the original “Zhou Yi” consisted solely of the core text, and it was only after Confucius that his commentaries were appended, forming the composite work as we know it today.

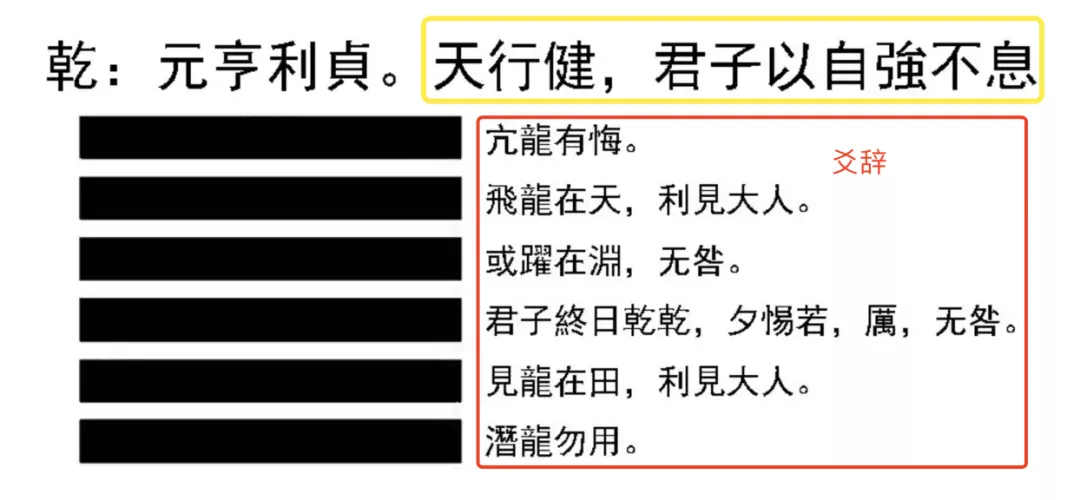

For those who might be perplexed, allow me to briefly illustrate using the Qian hexagram as an example.

In the diagram, the yellow portion represents Confucius’s contributions, while the red denotes the supplements added by the Duke of Zhou. The Qian hexagram itself is essentially the combination of two Qian trigrams (☰) as arranged by King Wen.

Having recounted the principal figures instrumental in the formation of the I Ching, I now turn my attention to what I consider its most perfect hexagram: the Humility hexagram.

Let us delve into the structure and symbolism of this configuration.

First, note that the hexagram is to be interpreted from the bottom upward. In the case of the Humility hexagram, the lowest line is a broken line—designated as the “initial six”; the second line is also broken, known as “six in the second position”; the third line is solid (a yang line) and is referred to as “nine in the third position”; the fourth line is broken (“six in the fourth position”); the fifth is similarly broken (“six in the fifth position”); and the topmost line is also broken, termed “upper six.”

Some may find these designations—such as “nine in the third position” and “six in the fourth”—confusing at first. Fundamentally, however, the lines of a hexagram are represented by only two symbols: 1 (a solid line) and 2 (a broken line), where 1 signifies yang and 2 signifies yin. Furthermore, odd numbers—1, 3, 5, and 9—are associated with yang, with 9 being the most potent, given that 1 + 3 + 5 equals 9. So why is yin represented by 6 rather than 8? The most plausible explanation is that 6 is the inversion of 9—in other words, yin is conceived as the antithesis or mirror image of yang.

This reasoning elegantly underpins the I Ching’s derivation of the yin-yang and Taiji principles, and indeed, nearly every hexagram has its corresponding inverse.

Now, let us further explore why the Humility hexagram is considered the epitome of perfection.

I shall begin by offering an interpretation of the Humility hexagram. Its lower trigram is Gen (☶), symbolizing restraint akin to a mountain that appropriately halts, while its upper trigram is Kun (☷), representing yielding and harmonious cooperation, reminiscent of the earth.

First Line (Initial Six): “Humility, Humility”

This phrase does not merely denote excessive modesty; it embodies a dual meaning. The modesty of the lower trigram (Gen) and that of the upper trigram (Kun) work in concert—the mountain below and the earth above jointly serve to guide and constrain one’s conduct. Hence, one must constantly exercise self-restraint, acknowledging that one’s abilities are still in development. Only when one reaches a state where no external restraints are necessary—yet one still refrains from transgression—does one embody the ultimate yielding nature of Kun. As Confucius once remarked, at the age of seventy one should “act according to one’s heart’s desire without overstepping proper bounds,” an ideal that is exceedingly rare.

Second Line (Six in the Second Position): “Resounding Modesty”

This line suggests that when you demonstrate genuine modesty and perform your duties with excellence, you may attract praise for your diligence, responsibility, capability, and humility. At such moments, however, you must remain cautious—if you allow such accolades to sway you, they may ultimately prove harmful. Excellence in one’s work is one’s duty, requiring no external inducement; becoming overly elated by modest praise can only yield modest rewards.

Third Line (Nine in the Third Position): “Laborious Modesty”

Here, positioned at the pinnacle of the mountain, the line signifies that an individual who distinguishes himself through significant contributions while remaining modest is truly admirable. Modesty without achievement is unworthy of praise; it is the fusion of considerable accomplishment and humility that captures the essence of the Humility hexagram.

Fourth Line (Six in the Fourth Position): “Exerted Modesty”

At this stage, one transitions from the modesty represented by the lower trigram (Gen) to that of the upper trigram (Kun). “Exerted Modesty” implies that one must actively manifest humility—extending it not only toward one’s superiors, which is comparatively easy, but also toward one’s subordinates, which is considerably more challenging.

Fifth Line (Six in the Fifth Position): “Protective Modesty”

By the time one reaches this line, it signifies that the individual is in a position of leadership. It is his responsibility to safeguard the prevailing spirit of humility and ensure that he does not inadvertently undermine it by his own actions.

Sixth Line (Upper Six): “Resounding Modesty”

Although this line is also termed “Resounding Modesty,” it differs from the second line. If the fifth line represents a leader, the topmost line embodies the senior statesman. A person of such stature must be circumspect, for one cannot afford to offend others arbitrarily. Instead, a leader of this magnitude must take it upon himself to correct those who lack humility, thereby preserving the collective spirit of modesty.

Having expounded upon the Humility hexagram, I now appreciate why all six of its lines are deemed auspicious. Its core tenets can be summarized as follows:

- Modest Demeanor in Life: Maintain a humble attitude without ostentatiously displaying your achievements or talents, thereby facilitating better integration into society and earning the respect and support of others.

- Timely Advancement and Retreat: Engage in actions that are appropriate for the moment—knowing when to push forward and when to step back—an embodiment of wisdom and acute situational awareness.

- Harmonious Coexistence: Foster amicable relations by cultivating humility, thereby reducing conflict and discord and nurturing a positive social environment.

At its very essence, the principle boils down to a single word: emptiness. By consistently maintaining a state of emptiness, you avert the perils of complacency and arrogance—which can stifle your capacity to learn. Self-satisfaction breeds the illusion that all success is solely deserved, thereby inviting envy and ill will. Thus, by embracing emptiness, you remain unpretentious and perpetually positioned for personal growth.

As for the remaining 63 hexagrams, those interested are welcome to leave a comment or obtain a copy of the I Ching for further exploration. Today’s discussion has primarily been an exploration of the philosophical dimensions of the I Ching; consider approaching its 64 hexagrams and 384 line statements as you would a profound work of philosophy. As the foremost classic of Chinese culture, the I Ching merits repeated study—do not dismiss it as inaccessible based on preconceived notions. These are my personal views, and I warmly welcome any further insights or commentary.