Four Repositories & Divination Cycles

What Are the “Four Repositories” in Chinese Divination?

In the study of Chinese metaphysics, the “Four Repositories” (四库) refer to the roles played by four specific Earthly Branches: Chen (辰), Xu (戌), Chou (丑), and Wei (未). These branches function as elemental reservoirs, each corresponding to one of the Five Elements (五行).

- Chou (丑) – The Metal Repository: As Chou belongs to the Metal element, it serves as a storehouse for Metal. It fosters the growth of the Earthly Branches Hai (亥) and Zi (子) while counteracting Yin (寅) and Mao (卯).

- Chen (辰) – The Water Repository: Chen corresponds to the Water element, nourishing Yin (寅) and Mao (卯) but conflicting with Si (巳) and Wu (午).

- Wei (未) – The Wood Repository: Wei is linked to the Wood element, supporting Si (巳) and Wu (午).

- Xu (戌) – The Fire Repository: Xu belongs to the Fire element and is known as the “Fire Vault.” It is in conflict with Shen (申).

These repositories act as energetic storage centers, influencing interactions between different branches in metaphysical calculations.

In feng shui and metaphysics, the concept of balance is often symbolized by yin yang jewelry, which embodies the harmony between opposing forces. Just as Chou (丑) stores Metal to foster equilibrium among Earthly Branches, yin yang jewelry serves as a tangible reminder of this cosmic balance.

What Is “Liu Jia Void” (六甲空亡)?

The term “Liu Jia Void” (六甲空亡), also known as Xun Kong (旬空), refers to missing Earthly Branches within a given ten-day cycle (旬). Each ten-day cycle consists of ten Heavenly Stems (天干) and twelve Earthly Branches (地支), meaning that two branches are absent in every cycle, creating a “void” (空亡).

For example, in the Jia Zi (甲子) cycle, the branches Xu (戌) and Hai (亥) are missing, so they are considered “void.” This pattern repeats for other cycles:

- Jia Xu (甲戌) cycle lacks Shen (申) and You (酉)

- Jia Shen (甲申) cycle lacks Wu (午) and Wei (未)

- Jia Wu (甲午) cycle lacks Chen (辰) and Si (巳)

- Jia Chen (甲辰) cycle lacks Yin (寅) and Mao (卯)

- Jia Yin (甲寅) cycle lacks Zi (子) and Chou (丑)

This concept is significant in destiny analysis, where an empty or “void” position can indicate either fortune or misfortune:

- If an inauspicious star falls into the void, it weakens its harmful effects, making it favorable.

- If a beneficial star falls into the void, it loses its power, making it unfavorable.

A classical poem describes this principle:

“Malignant stars rejoice in the void,

For when they vanish, fortune is restored.

But noble stars, when cast away,

Shall see their blessings much delayed.”

In personal fate analysis:

- A year branch void suggests limited parental support.

- A month branch void implies weaker ties with siblings and colleagues.

- A day branch void affects marital harmony.

- A hour branch void signifies less assistance from children.

- Multiple void positions indicate an unstable career, loss of reputation, or a life filled with hardship.

What Is “Solitude and Emptiness” (孤虚)?

“Solitude and Emptiness” (孤虚) is an ancient metaphysical principle used to assess the balance of energies in a given period. It emerges when the ten Heavenly Stems (天干) and twelve Earthly Branches (地支) are paired, leaving two branches unpaired—these are termed “Solitude” (孤) and their opposite branches are termed “Emptiness” (虚).

The concept is recorded in the Records of the Grand Historian (史记):

“When the celestial cycle is incomplete, solitude and emptiness arise.”

The placement of Solitude and Emptiness follows the same pattern as the Liu Jia Void, where the unpaired branches in each cycle are identified:

- In Jia Zi (甲子) cycle, Xu (戌) and Hai (亥) are Solitude, while Chen (辰) and Si (巳) are Emptiness.

- In Jia Xu (甲戌) cycle, Shen (申) and You (酉) are Solitude, while Yin (寅) and Mao (卯) are Emptiness.

Throughout history, scholars used Solitude and Emptiness for fate analysis. As the Han-era text Wu Yue Chun Qiu (吴越春秋) states:

“One must observe the cosmic energies, discern Yin and Yang, understand Solitude and Emptiness, and analyze existence and non-existence before making strategic decisions.”

Even Tang and Yuan dynasty scholars referenced this method for divination and governance.

What Are “Sui Yang” (岁阳) and “Sui Yin” (岁阴)?

“Sui Yang” (岁阳), also known as “Sui Xiong” (岁雄), refers to the ten Heavenly Stems (天干) in the calendar cycle, while “Sui Yin” (岁阴) refers to the twelve Earthly Branches (地支). This distinction was used in ancient calendrical systems.

As noted in Erya (尔雅):

“Tai Sui in Jia is called Yan Feng (阏逢), in Yi it is Zhan Meng (旃蒙), in Bing it is Rou Zhao (柔兆), and so forth…”

During the Western Han dynasty, astronomers assigned ten unique names to the ten Sui Yang years, corresponding to the sixty-year cycle:

- The first year is Yan Feng (阏逢) with She Ti Ge (摄提格)

- The second year is Zhan Meng (旃蒙) with Dan Yan (单阏)

- This continues in a sixty-year recurring cycle.

How Were Sui Yang and Sui Yin Established?

In ancient astronomy, the planet Jupiter (岁星, “Sui Xing”) was observed moving west to east in a twelve-year cycle, which led to the development of a twelve-part zodiac system (十二宫), also known as twelve star stations (十二星次).

To align Jupiter’s cycle with the traditional twelve Earthly Branches, scholars devised a hypothetical counteracting planet called Tai Sui (太岁), also called Sui Yin (岁阴). This system helped synchronize celestial observations with traditional astrology.

By the Western Han period, astronomers assigned ten names to match the ten Heavenly Stems, forming a dual system of Sui Yang (ten-stem cycle) and Sui Yin (twelve-branch cycle), which together created the full sixty-year cycle.

How Does the Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches System Work for Year Calculation?

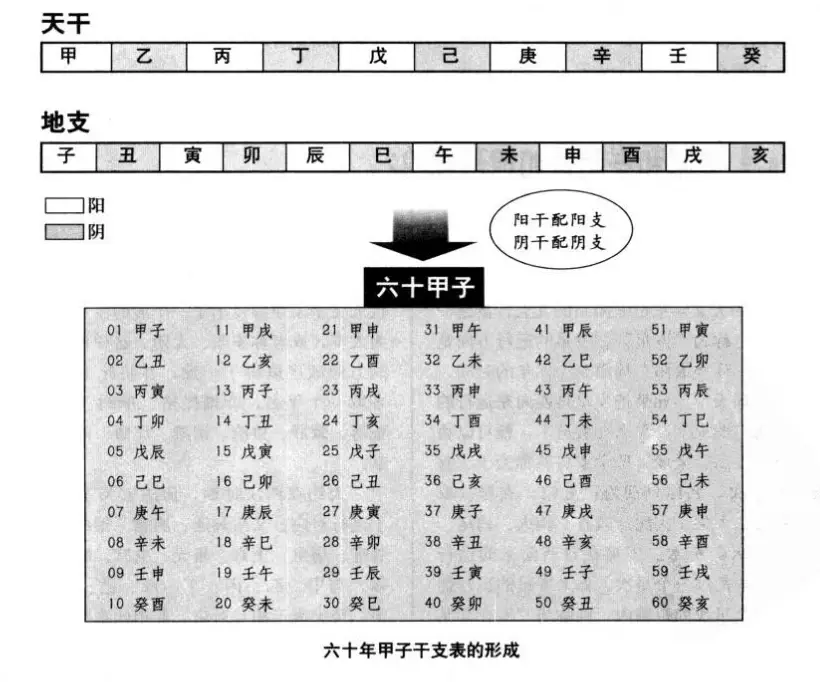

The Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches (干支) system is an ancient Chinese method for tracking years. By sequentially pairing the ten Stems (甲, 乙, 丙, etc.) with the twelve Branches (子, 丑, 寅, etc.), a complete sixty-year cycle (六十甲子) is formed.

For instance:

- 1949 (the founding year of modern China) corresponds to Ji Chou (己丑) year.

- This method was widely adopted since the Eastern Han dynasty (circa 85 CE) and remained in official use until the Republic of China era.

Even today, the traditional lunar calendar still follows this cycle for naming years.