He Tu & Luo Shu: Yin-Yang Cosmology

Explaining the He Tu Through Yin-Yang and the Five Elements

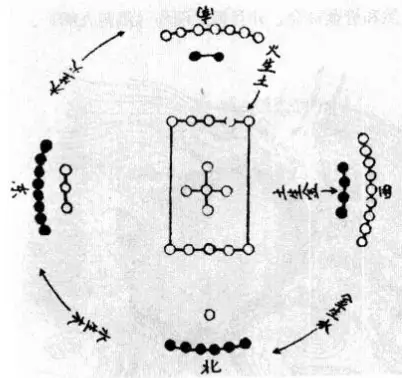

How can one interpret the He Tu using the principles of yin-yang and the five elements? The notion of “five elements generating the He Tu” generally refers to the “ten-number diagram.” Its structure is as follows: numbers one and six belong to the same clan and are both situated in the northern sector of the diagram; numbers two and seven, deemed companions, reside in the south; numbers three and eight, sharing a common path, are placed in the east; numbers four and nine, also regarded as friends, occupy the west; while numbers five and ten, mutually interdependent, are located in the center. In this illustration, white circles symbolize odd numbers, evoking the celestial realm and embodying yang—hence they are designated “celestial numbers.” Conversely, black dots denote even numbers, representing the terrestrial realm and embodying yin, thereby earning the appellation “earthly numbers.” The harmonious confluence of odd and even encapsulates the “union of heaven and earth” across five directions and reflects the interplay of yin and yang within the five elements.

Just like yin yang jewelry, which elegantly displays the balance and interplay between yin and yang elements in its design

The sum total of the He Tu is fifty-five—comprising twenty-five from the celestial numbers and thirty from the earthly numbers—thereby representing the numerical embodiment of heaven and earth. The numbers one through five are known as “generative numbers,” while those from six to ten are termed “completed numbers.” This division signifies the cyclic process whereby the five elements mutually generate and complete one another. Thus, the ten numbers inherent in the He Tu already embody the meanings of yin-yang and the five elements, which is why the diagram is also referred to as the “Five Elements Generative Number Diagram.”

In this schema, numbers one and six, positioned in the north, correspond to water in the five-element system; numbers two and seven, placed in the south, are associated with fire; numbers three and eight, located in the east, relate to wood; numbers four and nine, set in the west, pertain to metal; and numbers five and ten, residing in the center, are linked to earth. This arrangement is predicated on the following rationale: the north, as the origin of emerging yang qi, is paired with number one—and by extension with the completed number six—to signify that “where there is inception, there is fruition” (“Heaven’s one begets water; Earth’s six perfect it”). Likewise, the south, the birthplace of yin qi, aligns with number two to express “Earth’s two begets fire; Heaven’s seven perfect it.” In the east, where the sun ascends and yang qi steadily strengthens, the generative number three is matched accordingly (“Heaven’s three begets wood; Earth’s eight perfect it”). In the west, where the sun sets and yin qi correspondingly intensifies, number four is coupled to signify “Earth’s four begets metal; Heaven’s nine perfect it.” Finally, the central position, as the very core, unites the generative number five with the completed number ten to denote “Heaven’s five begets earth; Earth’s ten perfect it.” The association of odd numbers with yang and even numbers with yin underlines the principle that all phenomena in the cosmos depend on the harmonious union of yin and yang for their mutual sustenance.

Furthermore, if one rotates this diagram in a clockwise direction, it reveals the generative cycle among the five elements: water (represented by numbers one and six) engenders the wood of numbers three and eight; the wood, in turn, gives rise to the fire of numbers two and seven; this fire generates the earth of numbers five and ten; earth subsequently begets the metal corresponding to numbers four and nine; and finally, metal produces water, thereby completing the cycle. The four principal positions, when juxtaposed with the intermediate ones, illustrate the restraining (or overcoming) interactions among the elements—for instance, water and fire oppose each other vertically, while metal and wood counterbalance horizontally. This configuration vividly demonstrates the profound principle that within the cycle of generation there exists an intrinsic counterbalance—a “restraint within creation and creation within restraint.”

The Luo Shu, Yin-Yang, and the Five Elements

What is the relationship between the Luo Shu and the tenets of yin-yang and the five elements? The Luo Shu, often known as the “Nine-Number Diagram” or “Nine Palaces Diagram,” is configured as follows: “the nine numbers of the nine palaces—with nine at the apex and one at the base, three to the left and seven to the right, with two and four as the shoulders, six and eight as the feet, and five at the center—resembling the back of a turtle.” The total of its numbers is forty-five, and intriguingly, the sum of the three numbers in any horizontal row, any vertical column, or along either diagonal always equals fifteen.

Within the Luo Shu, odd numbers represent yang and symbolize the dynamic principles of the celestial order. Yang qi is said to originate in the north and, rotating in a clockwise direction, moves leftward; as it reaches the east, its intensity gradually increases, attaining its zenith in the south, before waning in the west. Thus, placing an odd number in the north indicates the nascent stage of yang; assigning the number three in the east signifies its growing strength; situating the number nine in the south denotes that yang has reached its peak; and placing the number seven in the west reflects its gradual decline. In contrast, even numbers embody yin, symbolizing the principles governing the terrestrial realm. Yin qi is believed to emerge in the southwest and, rotating counterclockwise, moves rightward; as it passes through the southeast, its potency increases until it reaches a climax in the northeast, before diminishing in the northwest. Accordingly, the even number two in the southwest indicates the onset of yin; the number four in the southeast marks its intensification; the number eight in the northeast represents its zenith; and the number six in the northwest signifies its gradual diminution. Notably, the directional assignments for the celestial (yang) and terrestrial (yin) as well as the odd-even designations are perfectly antithetical. The central placement of the number five thus epitomizes the harmonious integration between the “three heavens” and the “two earths.”

If the Luo Shu diagram is rotated counterclockwise, it elucidates the principle of elemental dominance: water (embodied by numbers one and six) is in opposition to fire (represented by numbers two and seven); fire, in turn, subdues metal (signified by numbers four and nine); metal overcomes wood (denoted by numbers three and eight); wood counteracts earth (symbolized by the central number five); and earth, ultimately, overcomes water (one and six). Moreover, the correspondence between the four principal and the four intermediate positions reflects the generative relationships among the five elements. For instance, the opposition of numbers one and nine with numbers six and four suggests that the metal of nine and four can give rise to the water of one and six; similarly, the pairing of numbers two and eight with numbers three and seven indicates that the wood of three and eight can produce the fire of two and seven. In this intricate interplay, even within the dynamics of overcoming there is an inherent potential for generation. The central number five, representing earth, plays a pivotal role in mediating and harmonizing the forces within the Luo Shu, ensuring that the sums along the vertical, horizontal, and diagonal lines all equal fifteen. This reflects a state of balanced stability in the cosmos, concealing within it the very essence of life. The allocation of odd numbers to the principal positions and even numbers to the subsidiary positions further mirrors the axiom that “yang is dynamic while yin is static,” encapsulating the process by which yang transforms into qi and yin coalesces into form.

The Luo Shu and the Twelve Tones

What, then, is the connection between the Luo Shu and the Twelve Tones? Within the He Tu, the five musical notes adhere to a principle of “generation every eight.” When these notes revolve around the central palace note, they give rise to the Twelve Tones. These twelve tonal positions can be corresponded with the nine palaces: numbers nine through one are matched with nine tones, while the subsequent three tones—represented by numbers six, five, and four—correspond to the remaining three tones. Arranged according to the positions of the twelve Earthly Branches, the locations of numbers two and eight are in a state of conflict, while numbers six, five, and four exhibit an inherent self-opposition. Specifically, numbers one, nine, and five symbolize the harmonious union of the branches Shen, Zi, and Chen; numbers seven, three, and five correspond to the union of Yin, Wu, and Xu; numbers four, six, and two reflect the alliance of Si, You, and Chou; and numbers four, six, and eight represent the union of Hai, Mao, and Wei. When arranged in the sequence from number two to nine and from number eight to three, one obtains the ordering of the tonal lengths of the Twelve Tones; arranging them from number eight to nine and from number two to three yields their generative sequence. Furthermore, among the twelve Earthly Branches, Chen is regarded as the Heavenly Gang and Xu as the River Chief—both occupying the most exalted positions—and are therefore paired with the central number five.