Hetu & Luoshu: Ancient Chinese Symbols

The Origins of the Hetu and Luoshu

What is the origin of the Hetu and Luoshu? In the Chinese tradition of divination, the term “He-Luo” first appears in the “Gu Ming” section of the Shangshu (Book of Documents) and is also mentioned in the “Zihan” chapter of the Lunyu (Analects). In Shangshu – Gu Ming, it is recorded: “Da Yu, Yi Yu, Tian Qiu, the Hetu is arranged in the east.” Similarly, the “Xiaocheng” chapter of the Guanzi states: “In ancient times, those who received the mandate were supported by a dragon-turtle; from the river emerged the diagram (Hetu), from the Luo emerged the book (Luoshu), and from the earth, the Yellow Chariot arose; nowadays, none of these three auspicious symbols can be seen.” Furthermore, the Zhouyi – Xici I affirms, “From the river emerged the diagram, from the Luo emerged the book; the sages based their practices on them.” Thus, the Hetu and Luoshu boast an ancient pedigree, having given rise to many subsequent theories in the realm of divination.

Legend of Fuxi and Da Yu

Legend holds that during the age of the ancient sovereign Fuxi, a dragon-horse emerged from the Yellow River in Mengjin County, located northeast of Luoyang, bearing the “Hetu” on its back, which it then presented to Fuxi. Inspired by this mystical diagram, Fuxi deduced the Eight Trigrams, which ultimately became the foundation of the Zhouyi (Book of Changes). Similarly, it is said that during the era of Da Yu, a divine tortoise surfaced in the Luo River in Luoning County, west of Luoyang, with a “Luoshu” inscribed on its back. Da Yu employed this revelation in his successful flood control endeavors, subsequently dividing the realm into nine provinces and formulating a system known as the “Nine Chapters” to govern society. This system was later transmitted in the Shangshu under the title Hongfan, from which the later doctrine of the Five Elements is said to have emerged. In this manner, subsequent scholars combined the yin–yang theory inherent in the Hetu with the five-element theory derived from the Luoshu to explain the dynamic laws governing all phenomena.The Hetu and Luoshu have also inspired various cultural expressions, including yin yang jewelry, which embodies the harmony of opposing forces.

Defining “He-Luo” Culture

What geographical region does “He-Luo” refer to? “He-Luo culture” designates the cultural sphere centered on Luoyang in Henan Province. It extends westward to Tongguan and Huayin in Shaanxi Province, eastward to areas around Rongyang and Zhengzhou in Henan, southward to Runan in Henan and Yingzhou in Anhui, and northward across the Yellow River into southern Shanxi and Jiyuan in Henan. Since ancient times, the He-Luo region has served as the political, economic, and cultural heartland of China—a core of the Central Plains, as reflected in the ancient expression “residing in the center of the world.” The ancient cultural heritage of this area is remarkably profound. Legends recount that “a dragon-horse bearing the diagram emerged from the river, and a divine tortoise presenting the book emerged from the Luo.” Here, “He” refers to the modern Yellow River, while “Luo” denotes the ancient Luo River. It is at the confluence of these two rivers that the essence of He-Luo culture was forged, encompassing the birthplace of Chinese civilization, from prehistoric pottery traditions to the seminal texts of the Yanhuang era such as the Luoshu and the Zhouyi. The influence of He-Luo culture and the Hetu has been vast, marked by its inclusiveness and expansive outreach to neighboring regions, ultimately spawning numerous other cultural systems.

The Debate over the Diagrams and Texts

What, then, is the “debate over the diagrams and texts” all about? Here, “diagram” refers to the Hetu and “text” to the Luoshu; hence, the controversy is also known as the “He-Luo controversy.” Since the Song Dynasty, scholars of divination have been embroiled in disputes over the authenticity of the Hetu and Luoshu, as well as whether the Eight Trigrams indeed originated from these symbols. The passage in Zhouyi – Xici II stating “From the river emerged the diagram, from the Luo emerged the book; the sages based their practices on them” indicates that this view was once widely accepted during the pre-Qin, Han, and Tang periods. However, by the end of the Tang Dynasty, the original Hetu and Luoshu had already vanished from sight. In the early Northern Song, the Taoist adept Chen Tuan revived public interest by proclaiming the Hetu, Luoshu, and the Pre-Heaven Tai Chi diagram, thereby sparking a debate between proponents who affirmed these texts and skeptics who questioned their antiquity. In the spring of 1977, during the archaeological excavation of the Shuanggudui site in Fuyang County, Anhui Province, a “Taiyi Nine Palaces Ancient Plate” was unearthed from the tomb of the Marquis of Ruyin of the Western Han. Its design was identical to that of the Luoshu, suggesting that the Luoshu must have appeared no later than the early Western Han period. Yet, controversy still lingers regarding the origins of the Hetu and the chronological precedence between these diagrams and the Zhouyi.

Evaluating the Credibility of “From the River Emerged the Diagram, from the Luo Emerged the Book”

Is the assertion that “from the river emerged the diagram, from the Luo emerged the book” credible? The Zhouyi – Xici I records this statement, which encapsulates an ancient tradition concerning the origins of the Hetu and Luoshu. According to this legend, during Fuxi’s era, a dragon-horse emerged from the Yellow River carrying the Hetu, which was then offered to the sage; and during the time of Da Yu, a divine tortoise emerged from the Luo bearing the Luoshu. This narrative is echoed by Yang Xiong of the Western Han—who remarked that “the order of the river and the dragon revealed to Da Yu the creation of the ‘Nine Categories’”—as well as in the Book of Han – Treatise on the Five Elements and the Shangshu – Gu Ming. Even the Han-era “Wei Shu” endorsed this account. Nevertheless, most later scholars of divination have largely repudiated this traditional view.

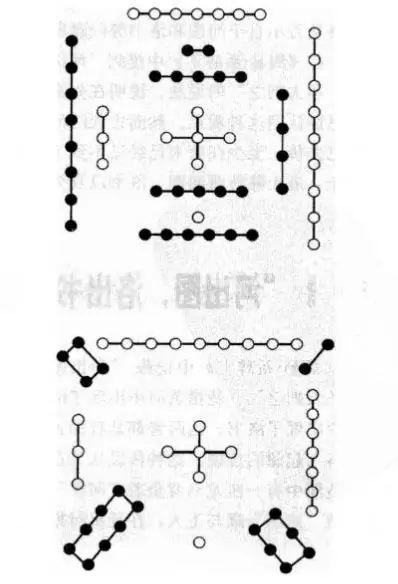

The Form of the Ancient Hetu

What, then, did the ancient Hetu look like? Legend tells that during Fuxi’s time, a dragon-horse emerged from the Yellow River whose back displayed a specific diagram. Its design featured, at the rear, one dot and six dots; at the front, two dots and seven dots; on the left, three dots and eight dots; on the right, four dots and nine dots; with five dots and ten dots positioned at the center. According to Yuan Wu Cheng in Yi Zuan Yan, “The Hetu originated during the reign of the Yellow Emperor. From the river emerged a dragon-horse whose back bore, at the rear, one and six; at the front, two and seven; on the left, three and eight; on the right, four and nine; and in the center, five and ten—resembling the swirling points of stars. The Yellow Emperor then employed these odd and even numbers, symbolic of yang and yin, to inscribe the trigrams.” These dots, reminiscent of stars in the night sky, were thus termed a “diagram,” and because it emerged from the Yellow River (anciently referred to simply as “the River”), it was named the “Hetu.” The ancient sages harmonized its odd–even pattern with the duality of yin and yang and graphically represented it to devise the trigrams.

The Formation of the Ancient Luoshu

How was the ancient Luoshu formed? In the era of Da Yu, a divine tortoise emerged from the Luo River, its back inscribed with mysterious patterns—the Luoshu. In this diagram, the numeral nine appears at the front, one at the rear, three on the left, seven on the right, and five in the center; additionally, two is inscribed at the front-left, four at the front-right, six at the back-left, and eight at the back-right. Yuan Wu Cheng, in Yi Zuan Yan, explains: “The Luoshu originated during Da Yu’s flood control. A divine tortoise emerged from the Luo, its back disassembled into characters: nine in the front, one in the back, three on the left, seven on the right, five in the center, two at the front-right, four at the front-left, six at the back-right, and eight at the back-left. As these disassembled figures resembled pictorial characters, they were termed a ‘book.’ Da Yu then expounded upon the numbers one through nine to outline the grand design of the nine provinces.” In essence, the Luoshu’s form is akin to deconstructing written characters into a visual diagram. Da Yu utilized these nine numbers to reform nature and administer society, and based on this he composed the Hongfan, outlining his governance principles.