I Ching Hexagrams:Bǐ Trigram

The term “比” (Bǐ)䷇ conveys the idea of closeness and mutual support. The Bǐ Hexagram is composed of the Kūn (Earth) and Kǎn (Water) trigrams. In terms of imagery, Kūn represents the earth and resides in the lower trigram, while Kǎn represents water and occupies the upper trigram. Water flowing on the surface of the earth signifies a harmonious and intimate connection, symbolizing “比” (closeness).

From the perspective of the lines (yáo), the Bǐ Hexagram consists of five yin (soft) lines and one yang (firm) line. The ninth position (Nine-Five), represented by a firm yang line in a noble position, serves as the focal point of mutual support and closeness for the surrounding yin lines. Despite its high position, the Nine-Five line, being firm and upright, also maintains closeness to the lower yin lines, which embodies the essence of “比.” As the primary line of the hexagram, Nine-Five attracts auspiciousness for the others through its intimacy and connection.

The Text of Bǐ:

“Bǐ. Auspicious. Original divination. Lasting rectitude. No misfortune.

Restless vassals will come; those who delay will face misfortune.”

Building relationships and mutual support with others is the path to good fortune. The term “original” signifies a second attempt, while “divination” (筮) refers to seeking answers through consulting the oracle. Among the 64 hexagrams in the I Ching, only the Méng (Youthful Folly) and Bǐ Hexagrams mention “divination.” Méng emphasizes sincerity in an initial inquiry, while Bǐ stresses caution in seeking answers a second time. This distinction arises because Méng concerns requesting guidance from others, where repeated inquiries indicate insincerity. In contrast, Bǐ pertains to mutual relationships, where acceptance is decided independently. A single inquiry may lack thorough consideration.

The Nine-Five line, occupying a central position in the upper trigram, exemplifies firm, balanced virtue, fostering closeness with the surrounding yin lines. A second divination is necessary to ensure one’s sincerity and virtue. If the Nine-Five line embodies the qualities of “original” (goodness), “lasting” (steadfastness), and “rectitude” (righteousness), it can accept the closeness of the yin lines without blame.

The phrase “Restless vassals will come” refers to regional rulers or leaders who are unsettled or uneasy, seeking mutual support and closeness. Those who are self-reliant, slow to build connections, or hesitant to act will face misfortune.

Example Interpretation:

Confucius’ disciple, Sima Niu, once lamented his lack of brothers. Zixia comforted him, saying, “A noble person conducts themselves with respect and maintains proper manners toward others. In this way, all people under heaven become like brothers. Why should a noble person worry about having no brothers?” This illustrates that a virtuous person, through righteousness and goodness, naturally fosters connections akin to brotherhood with others.

The hexagram’s text, “original, lasting, rectitude,” teaches us that fostering genuine relationships requires self-cultivation and moral integrity. Only by maintaining honesty and transparency can one avoid falling into cliques or fostering private alliances for selfish gain.

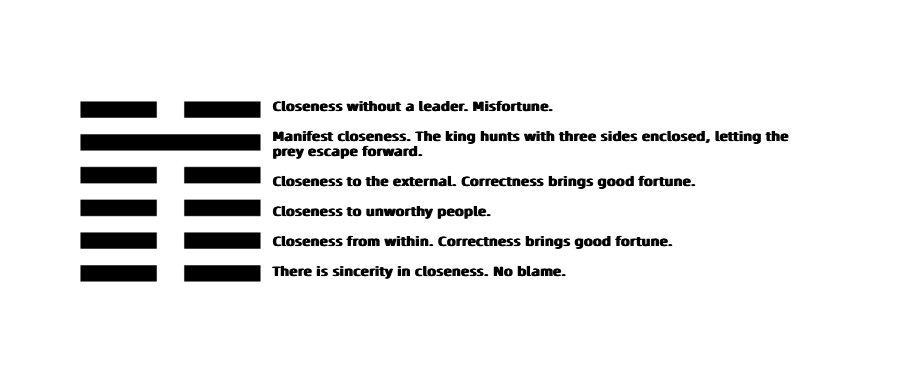

Initial Six (初六)

“There is sincerity in closeness. No blame. Like a simple jar filled to the brim. Ultimately, good fortune comes unexpectedly.”

The term “sincerity” (孚) refers to honesty and integrity at the core. “Full” (盈) means overflowing, and “jar” (缶)refers to a simple, unadorned earthenware vessel. The phrase “good fortune comes unexpectedly” suggests that blessings arise not from deliberate expectation but as a natural result of sincerity and virtue.

The Initial Six occupies the beginning of the Bǐ Hexagram, representing the need to uphold honesty and avoid wrongdoing. As a yin (soft) line at the very bottom, the Initial Six is in a lowly position, farthest from the noble Nine-Five yang (firm) line. To establish closeness with Nine-Five, the Initial Six must be filled with sincerity, akin to a plain jar filled to capacity, unembellished on the outside.

This imagery describes a virtuous person who does not rely on external appearances to win favor but instead seeks genuine connection through sincerity. In this way, even though Nine-Five is far from Initial Six, their eventual bond brings good fortune, arising naturally rather than through forced efforts.

Example Explanation:

During the Han Dynasty, the system of recruitment and recommendation allowed local governments to recommend virtuous and capable individuals, such as those known for integrity or filial piety, for service in the central government. Even commoners from humble backgrounds could achieve recognition and success by cultivating moral character and knowledge. This reflects the principle of “sincerity like a full jar,” where genuine self-improvement ultimately brings unexpected opportunities and blessings.

Six-Two (六二)

“Closeness from within. Correctness brings good fortune.”

Six-Two is a yin line in a yin position, situated centrally within the lower trigram. It is naturally aligned with the yang Nine-Five, representing an ideal balance of softness and firmness. “Closeness from within” means initiating connection with sincerity and self-reflection. Maintaining righteousness in forming relationships ensures good fortune.

Example Explanation:

Fàn Zhōngyān (范仲淹), a renowned statesman of the Song Dynasty, is a classic example of “closeness from within.” Devoted to the welfare of the nation, he earned Emperor Rénzōng’s favor. Tasked with defending the northwest border against the Xi Xia, he later proposed reforms to improve governance and strengthen the country. Despite opposition from corrupt officials, Fàn’s sincere and balanced approach to advising the emperor and nurturing talent garnered widespread admiration.

Six-Three (六三)

“Closeness to unworthy people.”

The Six-Three line, being yin but located in a yang (strong) position, lacks proper alignment and balance. It resides at the top of the lower trigram, symbolizing its departure from a grounded, stable position. Furthermore, Six-Three’s associations—Six-Four, Six-Two, and the top Six—are all yin lines, indicating that the connections it forms are unsuitable or unworthy.

In contrast to Initial Six and Six-Two, which foster closeness through virtue and righteousness, Six-Three fails to embody these qualities or form meaningful relationships. Its connection with the top Six, which opposes the principles of closeness, leads to the phrase “closeness to unworthy people”—a path to regret and shame.

Example Explanation:

Confucius once highlighted the difference between “three types of beneficial friends” and “three types of harmful friends”:

- “Friends who are upright, honest, and knowledgeable bring benefit.”

- “Friends who flatter, manipulate, or deceive bring harm.”

This reminds us to be discerning in our relationships. Aligning with virtuous individuals can inspire self-improvement, while forming bonds with unworthy people, marked by deceit or ill intent, leads to negative influences. The saying “You are who you associate with” aptly captures this caution.

Six-Four (六四)

“Closeness to the external. Correctness brings good fortune.”

The Nine-Five line represents a person of noble character and central authority, akin to a virtuous ruler or monarch. Positioned in the upper trigram, Nine-Five is firm, balanced, and upright. The Six-Four line, being soft and situated in the proper yin position, aligns with the principles of righteousness. While it does not correspond directly with Initial Six, it establishes a connection with Nine-Five externally, signifying the ability to approach virtuous individuals and follow wise leadership, which aligns with the path of righteousness, thus bringing good fortune.

Example Explanation:

During the late Edo period in Japan, the country faced political fragmentation as local domains (han) acted as semi-independent states. Emperor Meiji (1852–1912) initiated reforms known as the Meiji Restoration, leading to a proposal by four prominent domains—Chōshū, Satsuma, Tosa, and Hizen—to return their territories and population registries to the emperor (“Hanseki Hōkan”). This act of relinquishing feudal control in favor of centralized authority demonstrated the principle of “closeness to the external.” By aligning themselves with the emperor, these domains peacefully unified the nation, laying the groundwork for Japan’s modernization.

Nine-Five (九五)

“Manifest closeness. The king hunts with three sides enclosed, letting the prey escape forward.

The townspeople are unguarded. Good fortune.”

The word “manifest” (显) refers to openly demonstrating the principles of closeness. “Three sides enclosed” describes an ancient royal hunting method where the king would surround prey on three sides while leaving one side open for escape. This act symbolizes benevolence—capturing only those who willingly submit while sparing those who resist.

In the context of the hexagram, this hunting metaphor illustrates the king’s approach to governing:

- He does not pursue those who choose to leave (“lost prey” refers to the upper line, Six-Top, which has drifted away).

- He welcomes those who come willingly (represented by the other lines that seek closeness).

- His subjects (“townspeople”) live without fear or defensive measures, trusting his leadership.

This open and benevolent style of governance fosters harmony and ensures good fortune. True closeness arises when the ruler respects individual choices while creating an environment of trust and security.

Example Explanation:

Laozi once said:

“The best ruler is one whose existence is hardly known.

Next is one who is loved and praised.

Then, one who is feared.

And finally, one who is despised.”

In Laozi’s ideal, the most virtuous ruler governs with humility and integrity, allowing people to live freely without feeling oppressed. This principle aligns with “manifest closeness” (显比)—a ruler who leads without coercion, enabling his people to feel unburdened by authority. The idea of “letting the prey escape” and “unguarded townspeople” exemplifies this ideal, as it reflects trust, respect, and goodwill, which ultimately lead to good fortune.

Top Line (上六)

“Closeness without a leader. Misfortune.”

The term “leader” (首) here refers to an endpoint or guiding principle. In the hexagram, the Top Line (Six-Top) is a soft line positioned at the very end of the hexagram, located at the peak of the upper trigram (Kan), where danger is most intense. This line does not align with the Nine-Five, the central and virtuous line, but instead opposes it. Isolated and removed from the other lines, Six-Top finds itself in a perilous and alienated position. Its inability to establish proper connections from the beginning leads to an inevitable negative outcome, embodying the hexagram’s warning of “misfortune for the latecomer.”

Example Explanation:

China’s one-child policy, while highly effective in controlling population growth and improving overall birth quality, also produced unintended social challenges. Some only children, often referred to as the “little suns” of their families, grew up in an environment of excessive parental indulgence. Without siblings to interact with, these children lacked experience in collaboration and compromise. Overindulgence sometimes led to personalities that were solitary, self-centered, and difficult to cooperate with others.

This aligns with the concept of “closeness without a leader” (比之无首)—an inability to establish proper relationships results in isolation and a flawed character. While not all only children are affected in this way, those who lack proper guidance may develop traits that not only hinder their personal growth but also cause issues within society.

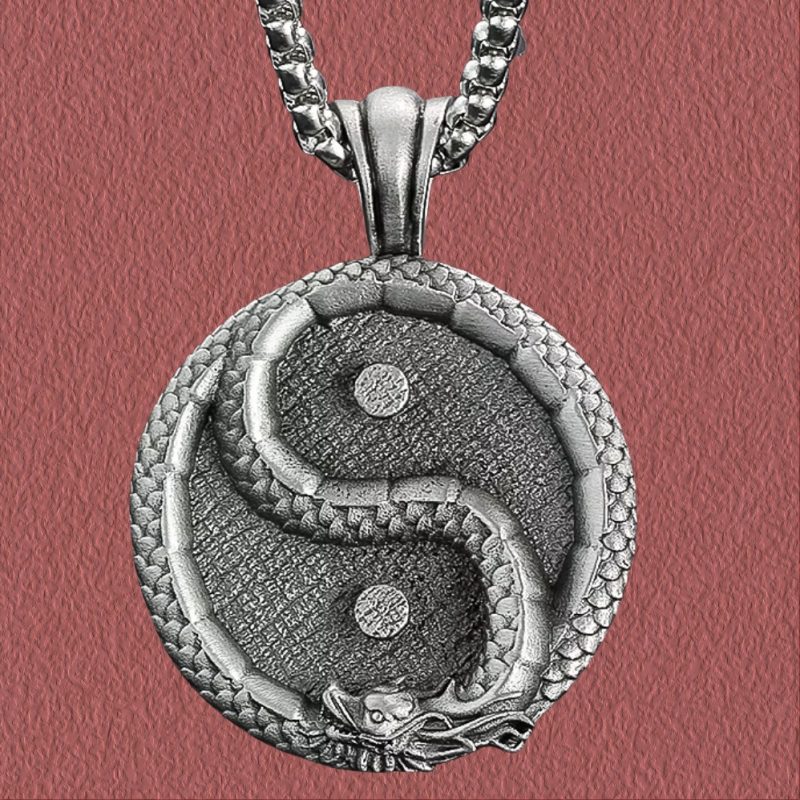

The Story of Sarah and the Dragon Yin-Yang Pendant

Sarah had always been a curious soul, drawn to the mysteries of the universe and the ancient wisdom of cultures around the world. One rainy afternoon, while exploring a small boutique in her neighborhood, she came across a striking piece of jewelry—a Chinese Dragon Yin-Yang Tai Chi Pendant Necklace. Its intricate design caught her attention immediately: the swirling yin-yang symbol held within a dragon’s embrace, radiating balance and harmony.

The shopkeeper, a kind elderly woman named Mei, noticed Sarah’s fascination and began sharing the story behind the pendant.

“This pendant represents more than just a beautiful design,” Mei explained. “It embodies the concept of 比 (Bǐ), which means closeness and mutual support. In ancient wisdom, it teaches that true strength comes from harmonious relationships—like water flowing over the earth, always connected yet balanced.”

Mei went on to describe the meaning of the hexagram associated with 比. She told Sarah about the yang line in the ninth position, symbolizing a leader who, despite their strength, remains connected and supportive of others. This resonated deeply with Sarah, who had been navigating a challenging time in her life.

Sarah worked in a fast-paced corporate world, where competition often overshadowed collaboration. She found herself longing for connections that weren’t transactional, for relationships built on trust and mutual respect. Mei’s words reminded her of the importance of fostering genuine bonds, both in her personal life and at work.

Sarah decided to purchase the pendant, not just as a piece of jewelry but as a symbol of her commitment to building meaningful connections. She began wearing it daily, and it quickly became her source of inspiration.

One day, during a critical team project at work, Sarah remembered the pendant’s lesson about the balance between strength and support. Instead of pushing her own ideas, she took time to listen and create space for her colleagues to share their thoughts. The result? A project that was not only successful but brought the team closer together.

The pendant also sparked conversations outside of work. When people complimented it, Sarah would share its story, spreading the wisdom of 比. She noticed how her relationships began to shift—friends opened up more, and strangers seemed drawn to her calm and balanced energy.

Months later, Sarah returned to Mei’s boutique, this time with a friend who had admired the pendant. Mei smiled knowingly.

“You see,” Mei said, “this pendant doesn’t just bring balance to its wearer; it inspires others to seek harmony too. That is the essence of 比—creating closeness that ripples outward.”

For Sarah, the Dragon Yin-Yang Pendant was more than an accessory. It became a reminder of the ancient truth: that through sincerity and mutual support, we can find harmony in even the most chaotic of worlds.