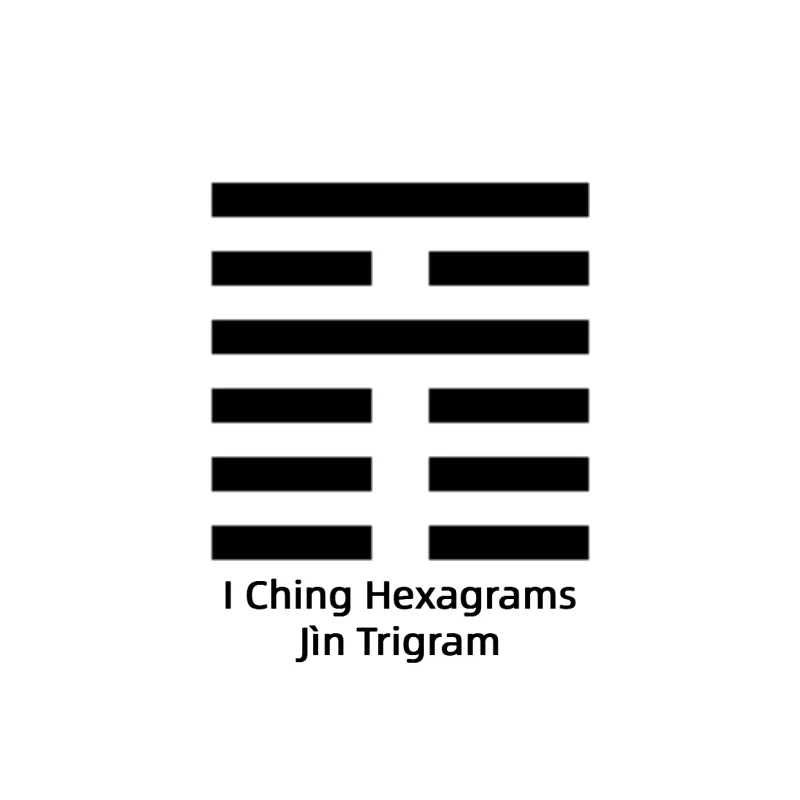

I Ching Hexagrams:Jìn Trigram

Jìn represents progress, where brightness and greatness gradually increase, much like the rising sun in the east.

The Jìn hexagram is made up of the Kūn and Lí hexagrams.

In terms of the hexagram symbols, Kūn represents the Earth, and Lí represents the Sun. With Kūn below and Lí above, this symbolizes the Sun slowly rising from the Earth, growing higher and brighter as it ascends. This is why the hexagram is called “Jìn” (progress).

In terms of its virtues, Kūn symbolizes obedience, and Lí symbolizes brightness. The combination of Kūn below and Lí above signifies that those in higher positions are wise, while those in lower positions show obedience.

The fifth line (liù wǔ yáo) is the core line of the Jìn hexagram. When in a time of progress, gentle lines rising will bring good fortune, but when strong lines rise, it brings danger and instability.

The phrase “Jìn. Kāng hóu yòng xī mǎ fán shù. Zhòu rì sān jiē” can be interpreted as:

“Kāng hóu” refers to a feudal lord who stabilizes and governs the country. Xī is synonymous with cì (to give or grant), meaning that those in lower positions offer tributes to those above them. Mǎ is extended here to represent lavish tributes. Fán shù means numerous offerings.

In essence, the Jìn hexagram represents a time when progress is accompanied by increasing brightness. Those in lower positions show obedience, and those in higher positions are wise.

This is compared to a feudal lord, who, having stabilized and governed the country, offers many horses as tributes to the king. The king receives them with the highest honors, meeting the lord three times a day. This metaphor shows the deep respect and trust between them. The ruler is wise, and the subjects are obedient, fostering mutual respect and trust—a state of ideal harmony.

This ideal state of harmony is similar to the balance represented by a Personalized Tai Chi Yin Yang Ring, which symbolizes the unity and harmony of opposites in life, just as the Jìn hexagram represents the harmonious relationship between rulers and subjects.

Example Interpretation:

Traditional Confucianism emphasizes the concept of reciprocal duties. It advocates for rulers to respect their ministers and for husbands and wives to show gentleness and harmony. Only with mutual respect can relationships be harmonious and collective goals be achieved.

In today’s world, especially with ongoing labor disputes, if employers focus on workers’ rights, provide a safe work environment, fair compensation, and proper time off, employees will likely cooperate with the company’s production and sales plans. In this way, the relationship between employers and employees will be like the “Kāng hóu yòng xī mǎ fán shù, zhòu rì sān jiē” metaphor: a harmonious collaboration, where the company can grow more effectively in a positive atmosphere.

Initial Sixth Line

Jìn rú cuī rú. Zhēn jí. Wǎng fú. Yù wú jiù.

“Jìn rú” means to rise or advance. “Cuī rú” means to hinder or block progress. “Wǎng” is interchangeable with “wú,” meaning “not” or “without.” “Wǎng fú” refers to not being trusted.

The Initial Sixth Line is a soft line positioned at the beginning of the Jìn hexagram. In contrast, the Fourth Line (represented by the jiǔ sì hexagram) is a strong line that occupies a passive position, neither in the right place nor in the center. The metaphor is that although the Initial Sixth Line wants to progress, it is blocked by the Fourth Line, which represents high-ranking officials close to the ruler. Thus, it portrays the image of “Jìn rú cuī rú” (progress blocked). In such a situation, the Initial Sixth Line must stay true to the righteous path in order to achieve good fortune. This is because the Initial Sixth Line, positioned in a lower position, will inevitably be unable to gain trust from those in higher positions in the short term. However, even though trust is not immediately granted, the Initial Sixth Line must maintain patience, avoid frustration from minor setbacks, and wait for the right time to act without causing mistakes.

Example Interpretation:

This is akin to how the famous Song Dynasty scholar Su Dongpo, when he was still a low-ranking official, was recognized by Emperor Yingzong. The emperor wanted to promote him greatly, but the prime minister, Han Qi, suggested that Su Dongpo start from a lower post to gain experience and then be entrusted with more important duties later, which would win him the respect of others. The emperor agreed with Han Qi’s advice, and Su Dongpo was assigned to a position in the historical archives. Instead of feeling resentful, Su Dongpo acknowledged the wisdom in Han Qi’s approach. Later, Su Dongpo was indeed promoted further, fulfilling his potential.

Second Line

Jìn rú chóu rú. Zhēn jí. Shòu zī jiè fú. Yú qí wáng mǔ.

“Jiè” means “great” or “large.” “Wáng mǔ” refers to the queen mother, symbolizing the Fifth Line.

The Second Line, a soft line in the passive position, is located in the middle of the Kūn hexagram and embodies a virtuous, balanced, and compliant nature. During a time of progress, the Second Line, with no direct connection to the Fifth Line, cannot advance quickly, which results in a feeling of sadness or frustration. At this time, the Second Line must also stay true to the righteous path in order to achieve good fortune and will eventually be rewarded with great blessings from the Fifth Line, symbolized by the “wáng mǔ” or queen mother.

Example Interpretation:

This can be compared to the famous Tang Dynasty poet Li Bai, who, due to his unwillingness to flatter the powerful before taking the imperial exams, failed to pass. The talented Li Bai was deeply discouraged, embodying the sentiment of “Jìn rú chóu rú” (progress hindered by sadness). However, later, when the Kingdom of Bohai sent a letter to the Tang Dynasty written in a foreign script that no one in the court could read, the official He Zhizhang seized the opportunity to recommend Li Bai to Emperor Xuanzong. Li Bai, who grew up in a mixed community of Han Chinese and foreigners and had a mother from the non-Han ethnic group, was proficient in the foreign language. Emperor Xuanzong immediately bestowed upon Li Bai a purple robe and golden belt, inviting him to the palace. Li Bai not only deciphered the letter but also wrote a response in the foreign language, reprimanding the Bohai Kingdom for its disrespect. After this event, Emperor Xuanzong greatly appreciated Li Bai’s talent, and Li Bai was rewarded with “shòu zī jiè fú, yú qí wáng mǔ,” receiving significant honor and recognition, eventually becoming a prominent figure in the imperial court.

Third Line

Zhòng yǔn. Huǐ wáng.

“Yǔn” means to trust or believe.

The Third Line is a soft line in a strong position. Although it is not in the correct place (the Third Line should ideally be in a central position), it is still in a place of strength. Typically, this would lead to regret, but the Third Line is placed above the Kūn hexagram’s Earth lines, which shows extreme compliance and gentleness. The lower hexagram (Kūn) consists of three soft lines, all of which are obedient to those in higher positions.

“Zhòng yǔn” means that everyone believes that the three soft lines of the lower hexagram (Kūn) are loyal and obedient ministers. A person who is trusted by the masses will certainly earn the trust and favor of those in higher positions. Therefore, the Third Line, leading the First and Second Lines, must bide its time and advance when the opportunity arises, eventually aligning itself with the wise ruler in the Fifth Line.

Example Interpretation:

This can be likened to the Eastern Han figure Chen Xi (104-187), who, despite not holding a high office, was highly respected for his virtue and wisdom. Therefore, whenever a vacancy arose among the three high officials of the court, many ministers would recommend him. The officials Yang Ci (the Grand Commandant) and Chen Dan (the Minister of Works) were both embarrassed and anxious because although they had not yet risen to high office, they felt they were outdone by Chen Xi’s moral stature. This demonstrates that when someone is trusted by the people, just like the “zhòng yǔn,” they will be valued by those in higher positions.

Fourth Line

Jìn rú shǔ. Zhēn lì.

The “shǔ” (rat) is often used metaphorically to represent greed and fear, as rats are known to steal and hide away, avoiding human presence. This metaphor implies that the Fourth Line is lacking in virtue and talent, and is jealous of others who are more capable.

The Fourth Line is a strong line in a passive position, occupying the lower portion of the upper hexagram. It is in a disordered, incorrect place and yet occupies a high position. It is greedy for the rewards of its position and afraid of others surpassing it. This fear leads it to block the advancement of the soft lines of the lower Kūn hexagram, hindering their progress. If the Fourth Line continues to act in this way without realizing its faults, it will inevitably bring disaster and misfortune.

Example Interpretation:

This can be compared to the rivalry between the military strategists Sun Bin and Pang Juan during the Warring States period. Although Sun Bin was far more talented than Pang Juan, Pang Juan was promoted by King Hui of Wei before Sun Bin. Later, when Sun Bin went to work for Pang Juan, the latter, driven by jealousy, feared that Sun Bin’s superior abilities would eventually outshine his own. In a fit of envy, Pang Juan had Sun Bin’s kneecaps removed. Fortunately, Sun Bin pretended to be insane and fled to the state of Qi, where he became a great general. Eventually, he led the Qi army to defeat the Wei army led by Pang Juan. Pang Juan, in the Battle of Maling, was outwitted and killed by a volley of arrows. This story shows the tragic outcome of a narrow-minded, greedy pursuit of fame at the expense of friendship and loyalty, much like the metaphor in the Fourth Line: “Jìn rú shǔ, zhēn lì” (progress blocked by greed, leading to danger).

Fifth Line

Huǐ wáng. Shī dé wù xù. Wǎng jí. Wú bù lì.

The Fifth Line is a soft line positioned in a prestigious and central place. While traditionally, a ruler’s position is associated with strength and decisiveness, the Fifth Line is ruled by gentleness, symbolizing a ruler who may feel regret or uncertainty. However, the Fifth Line is in the Lí hexagram, which represents brightness and wisdom, indicating that the ruler is a wise leader. Additionally, the three soft lines of the lower hexagram (Kūn) all obey the Fifth Line, which helps the ruler avoid regret.

The Fifth Line, occupying the central position of the upper hexagram, symbolizes a wise and gentle king. The ruler should trust his ministers and be honest with them, avoiding arbitrary decisions or personal gain. By acting with this openness and trust, the ruler will find success and prosperity without any hindrances.

Example Interpretation:

This mirrors the story of Emperor Zhao of Han (Liu Fuling, 94 BCE – 74 BCE). Although young when he ascended the throne, he was wise beyond his years. When some officials tried to frame General Huo Guang, who had been appointed to govern by Emperor Wu’s will, Emperor Zhao not only defended Huo Guang but also reprimanded those who sought to undermine him. He placed even more trust in Huo Guang, which led to greater dedication to governance. As a result, Emperor Zhao’s reign was marked by good governance and peace for the people.

Ninth Line

Jìn qí jiǎo. Wéi yòng fá yì. Lì. Jí wú jiù. Zhēn lìn.

“Jiǎo” refers to a sharp, hard object, symbolizing the extreme position of the Ninth Line in the Jìn hexagram. “Fá yì” means to attack or rectify one’s own city, implying self-reflection and governance. The Ninth Line should redirect its overly rigid, aggressive desire to advance into self-discipline and self-examination. By focusing on improving the self, even in the face of difficult circumstances, one can achieve success without misfortune. A person who governs themselves with strict discipline and honesty will remain steadfast on the path of virtue. However, the Ninth Line, being at the peak of the hexagram, may focus solely on progress and fail to recognize when to stop. If one clings too rigidly to this path without adaptability, it may lead to arrogance or self-righteousness.

Example Interpretation:

This idea aligns with the Neo-Confucian philosophy of the Song Dynasty, which emphasized restraining personal desires and returning to the fundamental principles of morality. The spirit of self-governance and unwavering effort is an embodiment of human dignity, as seen in the phrase “Jìn qí jiǎo, wéi yòng fá yì.” However, if one becomes overly rigid and unyielding—like a woman refusing to marry a second husband or living life too seriously—one risks becoming too narrow-minded, as indicated by “zhēn lìn” (unnecessarily stubborn), losing the true meaning of self-restraint and returning to propriety.