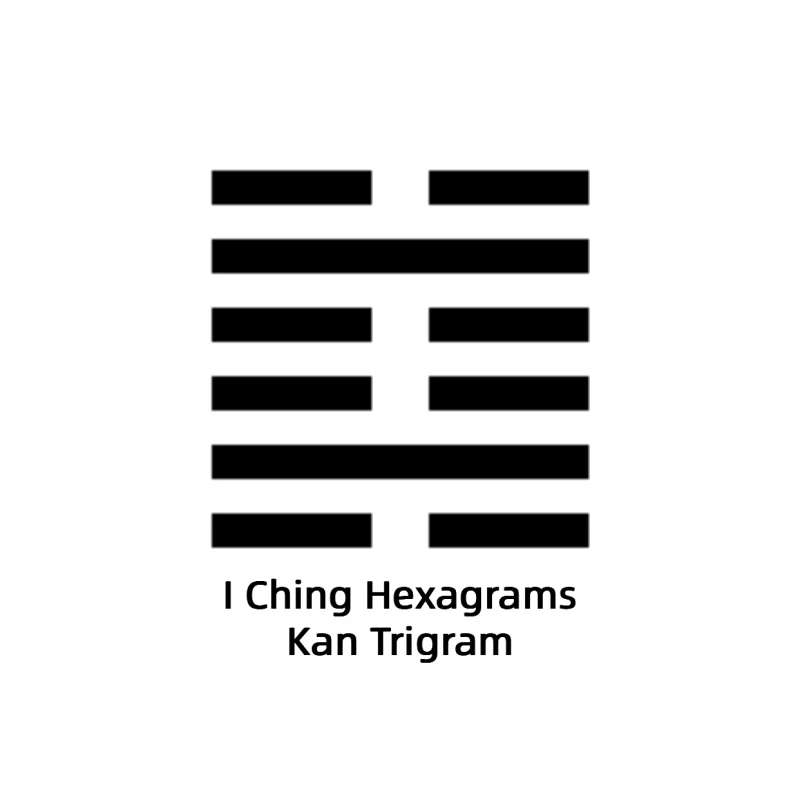

I Ching Hexagrams:Kan Trigram

The trigram “Kan” is symbolized by flowing water, and its virtue is danger and entrapment. The three-line Kan trigram is a yang trigram, with one yang line in the center and two yin lines above and below it. This represents a yang line trapped between two yin lines, signifying danger and entrapment. The Kan hexagram is formed by the stacking of two Kan trigrams.

The virtues of the eight trigrams are as follows: Qian (Heaven) represents strength and vigor, Kun (Earth) represents gentleness and compliance, Zhen (Thunder) represents movement, Gen (Mountain) represents stillness, Li (Fire) represents attachment and beauty, Kan (Water) represents danger and entrapment, Xun (Wind) represents penetration, and Dui (Lake) represents joy and harmony. Among these, only the Kan trigram’s virtue of danger and entrapment is considered inauspicious and is not favored by the noble person. Therefore, only the Kan hexagram is named “Xi Kan” (习坎), where “Xi” means repetition or habituation. “Xi Kan” implies danger within danger, suggesting that one must become accustomed to danger in order to overcome it. Just as flowing water contains hidden dangers, those who are skilled in swimming can navigate the waters freely without drowning. This illustrates that one must first become accustomed to perilous environments before they can navigate and escape them.

Xi Kan. You Fu Wei Xin. Heng. Xing You Shang.

“Xi Kan” refers to becoming familiar with danger and entrapment in order to overcome it. In the Xi Kan hexagram, the fifth and second lines are both yang lines, occupying the central positions of the upper and lower trigrams, respectively. This symbolizes the presence of yang energy in the center, representing sincerity and integrity, hence “You Fu” (having sincerity). “You Fu Wei Xin” means maintaining a sincere and focused mind. Because of this sincerity and focus, one can achieve success and smooth progress. Water naturally flows downward, moving continuously without stopping, flowing without filling up. Despite encountering countless obstacles and winding through dangerous terrain, it never loses its integrity and ultimately flows into the sea. When faced with multiple layers of danger, one must take action to escape the peril; stagnation will not lead to escape. Therefore, “Xing You Shang” means that taking action to escape danger is commendable and worthy of encouragement.

Example: During the War of Resistance against Japan, although the situation was perilous and the process was extremely arduous, everyone realized that the war was a matter of life and death for the nation. At that time, the entire country was united, “You Fu Wei Xin” (maintaining sincerity and focus), sharing a common hatred for the enemy. The saying “One inch of rivers and mountains, one inch of blood; one hundred thousand youths, one hundred thousand soldiers” reflects the strong will and brave actions that ultimately led to final victory.

First Six (Chu Liu).

Xi Kan. Entering the abyss of Kan. Misfortune.

The “abyss” (窞, dàn) refers to a deep pit. The First Six lies beneath the stacked Kan trigrams. As a yin line occupying a yang position, it symbolizes a weak nature attempting to act with force. Trapped in danger, it lacks the strength to escape and instead sinks deeper into the abyss. This line embodies the idea of “petty individuals gambling with danger for blind luck.” When faced with peril, such individuals abandon integrity, hoping to evade consequences through deceit—a path that inevitably leads to misfortune.

[Example] The American Mafia originated from Sicily, Italy. Many Sicilian immigrants, facing harsh conditions, succumbed to temptation and “entered the abyss,” sinking deeper into crime. Yet, as the saying goes, “The law is vast and unyielding; though its net seems loose, nothing escapes.” Eventually, their crimes came to light, and they faced imprisonment.

Nine in the Second Place (Jiu Er).

Danger in the abyss. Seek modest gains.

Nine in the Second Place, a yang line trapped between two yin lines, symbolizes being mired in danger. However, as a firm and centered line in the lower trigram, it possesses the strength to navigate peril and act with measured resolve. Still, since the upper trigram remains Kan (danger), complete escape is impossible. Though unable to fully overcome adversity, Nine in the Second can leverage its inner fortitude to secure small, practical victories.

[Example] In the late Qing Dynasty, China faced internal chaos and foreign invasions. Amid this existential crisis, reformers like Zeng Guofan, Li Hongzhang, and Zuo Zongtang launched the “Self-Strengthening Movement” (1860s–1890s), importing Western industrial technology to revive the nation. While the movement could not save the collapsing dynasty or fully modernize China—hampered by internal corruption and external pressures—it achieved “small gains” by laying early groundwork for China’s modernization.

Six in the Third Place (Liu San).

Peril on all sides. A precarious pause. Entering the abyss. Do not act.

“Coming and going” refers to retreating or advancing. “Pause” (zhen) implies a temporary rest without true stability. Six in the Third Place sits between the upper and lower Kan trigrams. Whether retreating or advancing, danger lurks everywhere—hence “peril on all sides.” As a yin line in a yang position, it lacks balance and integrity, making even its resting place unstable. The warning “Do not act” urges Six in the Third to pause where possible. Though this won’t escape danger, it prevents sinking deeper into the abyss. Acting recklessly would worsen the situation, inviting disaster.

[Example] If trapped in an elevator during a power outage, panic or forcing the doors open risks greater harm. Instead, staying calm, waiting patiently, and signaling for help aligns with “a precarious pause”—it avoids deeper peril even if immediate escape is impossible.

Six in the Fourth Place (Liu Si).

A jug of wine, two bowls of grain, offered in earthenware. Present sincerity through clarity. No blame in the end.

The “jug” (zun) was an ancient wooden wine vessel; “bowls” (gui) were ritual grain containers; “earthenware” (fou) refers to simple pottery instruments. “Clarity” (you) here symbolizes a window—a source of light and openness. Six in the Fourth, a yin line in its proper place, supports the strong and centered Nine in the Fifth (the ruler) during times of crisis. Together, they embody harmony between firmness and flexibility to overcome danger.

The modest offerings—wine, grain, and humble music—symbolize sincerity and frugality. “Presenting sincerity through clarity” means appealing to a ruler’s enlightened mind. To advise a leader effectively, one must speak to their reason and virtues (the “bright window”), not their biases. Blunt criticism often breeds resistance, but tactful persuasion rooted in shared values can succeed. Like the saying “meeting the master in the alley” (from the Kuai hexagram), this approach navigates adversity with grace, turning initial friction into resolution.

[Example] During the Spring and Autumn Period, Duke Ling of Jin sought to build a lavish tower, threatening death to dissenters. Minister Xun Xi avoided direct confrontation by performing a balancing act with eggs in front of the duke. As the tower of eggs teetered, Xun Xi warned, “Your extravagance destabilizes the state like this fragile stack.” By appealing to the duke’s sense of spectacle and metaphor—a “bright window” in his mindset—Xun Xi averted disaster without provoking wrath.

Nine in the Fifth Place (Jiu Wu).

The abyss does not overflow. Just enough to level. No blame.

“Just enough” (zhi) implies perfect balance. “The abyss does not overflow” reflects water’s nature to flow without excess. Nine in the Fifth, a yang line in its rightful position and the center of the upper trigram, embodies strength tempered by moderation—like a river nearing the sea, its currents steady and controlled. Though still within danger, it avoids peril by harmonizing with circumstance. The abyss loses its menace, hence “no blame.”

[Example] During the Spring and Autumn Period, Prince Chong’er of Jin endured years of exile, surviving countless dangers. When chaos engulfed Jin, he returned with Duke Mu of Qin’s aid, ascended the throne as Duke Wen of Jin, and forged a legendary reign. His resilience and adherence to principled leadership—akin to “flowing without overflowing”—allowed him to navigate peril and emerge victorious.

Top Six (Shang Liu).

Bound by triple-strand ropes, confined in a thicket of thorns. Three years without release. Misfortune.

“Bound” (xi) means tied; “triple-strand ropes” (hui) are thick cords of three twisted fibers. Top Six, a yin line at the peak of danger, could escape but instead clashes with Nine in the Fifth (the ruler), creating new obstacles. By defying the natural order, it invites harsh punishment: bound and imprisoned in a symbolic “thicket of thorns” for years. Such rebellion against the Dao inevitably brings calamity.

[Example] In the late Qin Dynasty, the scheming minister Zhao Gao sought to manipulate Emperor Ziying as a puppet. But Ziying outmaneuvered him, trapping and executing Zhao. Like Top Six, Zhao Gao exploited crisis for personal gain rather than serving the greater good, leading to his downfall—a fate as inescapable as being “bound in thorns.”