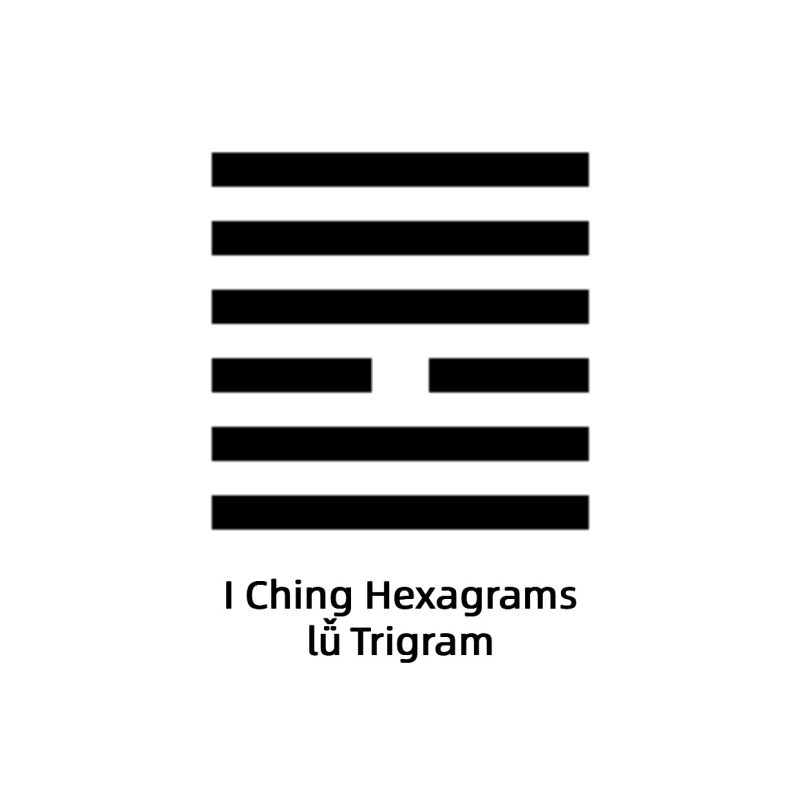

I Ching Hexagrams:lǚ Trigram

The term “履” (lǚ) refers to the practice of carrying out duties and adhering to proper etiquette. The “履” hexagram is made up of the Dui and Qian trigrams.

From the perspective of the hexagram’s symbolism, the lower trigram Dui represents a marsh or lake, which is at the lowest point, while the upper trigram Qian represents the sky, which is at the highest point. Among the eight trigrams, Qian is the most revered,output:output:output: and Dui is the most humble. The combination of heaven above and the marsh below symbolizes the concept of respect and hierarchy, where each level has its own position and cannot overstep it—much like following proper rituals. This is the essence of “履.”

Looking at the virtues of the hexagram, Qian is the strongest and most vigorous among the three-line hexagrams, while Dui is the most harmonious. The harmonious Dui follows the strong Qian, suggesting that only by adhering to ritual and propriety, like stepping carefully on thin ice, can one avoid danger. Therefore, when in the state of “履,” the key is to embrace a gentle and compliant attitude.

In the six lines of the “履” hexagram, any position associated with the Yin (receptive) energy, such as lines 2, 4, and the top line, indicates that success is achieved through humility and flexibility.

The phrase “履虎尾” (lǚ hǔ wěi), meaning “to step on the tiger’s tail,” is another significant symbol in this hexagram. A tiger is a fierce beast, capable of biting and causing harm. However, the hexagram suggests that when one steps cautiously behind the tiger’s tail, with the harmonious and serene nature of Dui, there is no danger of being bitten. On the contrary, success will be achieved. This teaches us that if one conducts themselves with humility, follows proper protocol, and remains cautious, even in the most dangerous situations, they can avoid harm and emerge victorious.

A well-known saying that reflects this idea is, “Serving the ruler is like walking with a tiger.” While Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty was a wise and capable ruler, he once mistakenly trusted malicious rumors about General Li Jing after he had successfully subdued the Turks. However, Li Jing, understanding the importance of self-preservation, responded with humility and respect, easing the emperor’s suspicions. In doing so, he was able to live a long and prosperous life. Had he become defensive and insisted on arguing his case, he may have fallen deeper into the trap set by his enemies. Instead, by following the way of “履,” Li Jing avoided disaster and prospered.

In essence, the “履” hexagram teaches us that by walking with humility and adhering to proper conduct—especially in difficult or dangerous circumstances—we can achieve success without falling into harm’s way. It’s not just about being passive or submissive, but about knowing when and how to maintain a respectful and cautious approach in the face of challenges.

Sì lǚ wǎng, wú jiù (“素履往,无咎”)

“素” here refers to simplicity and purity, free from embellishment. In the context of the “履” hexagram, the first line is associated with a solid yang energy in its initial position, meaning that one can move forward while adhering to ritual and propriety. However, the essence of “ritual” (礼, lǐ) lies in the heart’s genuine respect and humility, not in external formality. In other words, the outward gestures and ceremonies are secondary to the sincere intention of reverence. In The Analects (论语), Confucius mentions “hùi shì hòu sù” (绘事后素), which refers to the idea that the finishing touches on a painting only make sense once the basic structure is in place. The “素” in the first line of the hexagram thus signifies that true virtue and intention must precede any formality.

When the first line says “素履往,” it means that someone moves forward with pure intentions, unaffected by personal emotions or external circumstances. This is similar to the concept in the Doctrine of the Mean (中庸) that a “gentleman stays true to his principles” (君子素其位而行). This line suggests that a person who remains grounded in their virtues, who acts according to their beliefs with humility and respect, will not face misfortune.

Example:

Take Confucius’ disciple, Yan Hui. Though Yan Hui lived in a humble, dilapidated house and faced difficult circumstances, he remained at peace because he adhered to his ideals and acted with genuine humility. Confucius famously said of him, “Even in the face of hardship, Yan Hui did not change his joy.” Yan Hui’s heart, “for three months, did not deviate from benevolence” (其心三月不违仁), and as a result, he was revered and later called the “Second Sage” (复圣), second only to Confucius himself.

Lǚ dào tǎn tǎn, yōu rén zhēn jí (“履道坦坦,幽人贞吉”)

The second line of the “履” hexagram is associated with the position of Yin energy (receptive), which suggests that flexibility and moderation are key. This line depicts a person walking on the “broad and level way” of the Dao, meaning they follow the middle path with balance and integrity. In the world, the central path of a road is generally the smoothest, while the edges are uneven. The phrase “幽人” refers to someone who is withdrawn, tranquil, and unperturbed by the world. This is in contrast to the “武人” (militaristic or forceful person), who is stubborn, reckless, and disruptively self-willed. The “幽人” exemplifies someone who remains composed and true to their principles, avoiding conflict and walking steadily on the “wide, smooth path” of righteousness.

In this context, the line advises that only someone who is serene, modest, and withdrawn—who remains undisturbed by external distractions—can stay on the straight path and achieve success. It’s a reminder that one’s inner calm and self-discipline are what allow them to walk the “smooth way” in life, regardless of external conditions. If one’s mind is restless, no amount of external stability will bring them peace.

Example:

A good example of this principle is Zhang Liang (??–前189 BCE), one of the founding heroes of the Han Dynasty. He played a crucial role in helping Liu Bang secure the throne, but after the foundation of the Han Dynasty was established, Zhang Liang withdrew from the political scene, choosing to retire into seclusion. He understood the nature of power—how those who share in the struggle often cannot share in the prosperity. By stepping back from court life, Zhang Liang avoided the fate of other loyal ministers who were purged after the regime stabilized. In doing so, he lived a peaceful life away from the turmoil that often comes with power, illustrating the wisdom of remaining “幽人”—withdrawn, peaceful, and true to one’s principles.

Expanded Understanding:

The central theme here is about adhering to one’s principles and maintaining a sense of humility and peace regardless of external pressures. The first line (“素履往”) encourages walking the path of ritual and propriety with a pure heart, while the second line (“履道坦坦,幽人贞吉”) emphasizes that those who walk with tranquility and moderation, staying true to their values and not swayed by the world, will succeed in the long term.

Both lines present the concept of balance—whether it’s balancing one’s intentions with humility or balancing one’s position in life with inner peace. These principles, though framed within the ancient context of Confucian teachings, are timeless and applicable to many aspects of modern life. In both cases, the wisdom of the hexagram teaches that success comes not from forceful actions or external accomplishments, but from an inner steadiness and an adherence to a moral compass that remains unmoved by external circumstances.

“Miao neng shi. Bo neng lü. Lü hu wei. Tie ren xiong. Wu ren wei yu da jun.”

“Miao” refers to being unable to see properly, often due to squinting or having limited vision. “Bo” refers to having a limp, a condition where one’s walking is impaired, often due to an uneven or crooked leg. In this line of the hexagram, we are told that, although someone may be able to see or walk, they do so in a distorted, uneven manner. This is a metaphor for someone who has the potential or capability but lacks the proper alignment, balance, or understanding to move forward correctly.

The line also refers to a person in a position of Yang energy (strong, active) who is expected to act with force but who is, in fact, naturally inclined to be softer (Yin energy). This person, though they might have the will to take action, is unable to do so with the right kind of force, often resulting in a situation where they act recklessly or without full comprehension, much like trying to walk with a limp or squinting to see. The text warns that if such a person acts too hastily or without caution, they will likely find themselves in a dangerous situation—“stepping on a tiger’s tail,” a metaphor for walking into peril without the proper precautions.

In ancient times, stepping on a tiger’s tail was considered a reckless act that could lead to harm, so this line highlights the dangers of overconfidence or acting without preparation. It further says, “Tie ren xiong,” meaning that a person who continues down this dangerous path is bound to face misfortune. However, if a warrior (Wu ren) seeks to do something in service to a great lord, there can be value in that reckless bravery, even if it leads to death.

Example:

Consider the story of Zhao Kuo during the Warring States period. Zhao Kuo, the son of a renowned general, took charge of the Zhao army when his father could no longer lead. Young and overconfident, Zhao Kuo was eager to prove himself. However, despite his theoretical knowledge of military strategy, he lacked real battlefield experience. His overconfidence led him to make poor decisions, and during the Battle of Changping, his army of 400,000 soldiers was wiped out by the Qin general Bai Qi. Zhao Kuo himself died in battle. His story is a prime example of the idea that one can have the ability to see or walk,output: but if they are misaligned or unprepared, they will fail.

“Jiu si. Lü hu wei. So so. Zhong ji.”

“Su su” here refers to a trembling or cautious state. Line 64 portrays someone in a dangerous position (again, stepping on the tiger’s tail) but who is able to navigate that danger with a cautious and humble attitude. Though fear is present, it is acknowledged and used wisely, leading to a favorable outcome. The person in this line understands the severity of the situation and acts with restraint, knowing that excessive boldness or arrogance could be disastrous. They are, in essence, trembling with caution but moving forward with careful wisdom.

In this case, the individual is in a perilous situation but uses their strength with a sense of restraint and humility. The line advises that, while being fearful or cautious is not inherently negative, it should be balanced with the ability to act with wisdom. This balance allows the person to avoid disaster, and the line ends with the promise of eventual success if they proceed with care and mindfulness.

Example:

A historical figure who embodies this cautious wisdom is Sima Qian, the great historian of the Han Dynasty. Sima Qian suffered a grave personal setback when he defended General Li Ling, who had surrendered to the Xiongnu. The emperor, angered by this defense, ordered Sima Qian to undergo castration. This traumatic experience deeply altered Sima Qian’s approach to life. In his later years, he adopted a much more cautious and thoughtful attitude, fully aware of the dangers of political power struggles. When a close friend, Ren An, was condemned to death, Sima Qian chose to distance himself and wisely avoided getting involved. His careful, humble attitude allowed him to continue his work as a historian and live out his years in relative peace. His story demonstrates that “su su” (trembling with caution) can lead to long-term success, even when faced with grave danger.

Expanded Interpretation and Context:

Both lines from the hexagram teach important lessons about balance, caution, and wisdom in the face of danger. The first line warns against recklessness and overconfidence—whether due to arrogance or lack of preparation. It highlights the perils of acting without full alignment or understanding, with the metaphor of stepping on a tiger’s tail as a stark warning of the risks involved.

The second line, in contrast, emphasizes that success can still be achieved in dangerous situations if one approaches them with careful deliberation and humility. The key here is not to be paralyzed by fear but to use it as a tool for wise decision-making. By remaining cautious, thoughtful, and aware of the risks, one can navigate even the most perilous circumstances without falling victim to disaster.

In modern terms, these lines are a reminder that success is not always about boldness or brute force. Sometimes, the most effective way to handle challenges is with quiet caution, wisdom, and the ability to adapt to changing circumstances. Whether in business, relationships, or personal growth, this hexagram suggests that a balanced approach—knowing when to take risks and when to step back—is often the most successful path forward.

“Guai lü. Zhen li.”

In this line, “guai” refers to decisiveness or resoluteness. The person here is in a position of power, typically the king or ruler, represented by yang energy (strength, assertiveness) placed in a central and authoritative position in the upper trigram. This figure holds the qualities of strength, wisdom, and the ability to make firm decisions. They possess the ability to see clearly and make judgments with great authority, yet their power must be tempered with humility and wisdom.

The warning here is that if the ruler becomes overly self-confident, relying too much on their own intellect, wisdom, or authority without regard for others’ opinions, even the humblest of voices, they risk becoming disconnected from the greater truth. If the ruler begins to believe they are infallible, they will lose their balance and stray from the dao of rightful leadership. The I Ching advises the ruler to always maintain a sense of caution and humility, listening to all voices, no matter how insignificant they may seem. Only through this can they truly govern in a way that benefits the entire nation, radiating wisdom and fairness.

Example:

A prime historical example of the dangers of overreaching power is Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang, the founding ruler of the Ming Dynasty. While he was diligent and determined to consolidate power, he abolished the position of the prime minister, taking all the power for himself. In the beginning, he was able to govern well. However, his descendants lacked the same leadership qualities, and without the stabilizing force of a prime minister, the Ming Dynasty’s power structure began to weaken. This led to widespread corruption, with eunuchs and power-hungry ministers gaining control. The decision to eliminate the prime minister position is often seen as the root cause of the Ming Dynasty’s eventual political decay.

“Shang jiu. Shi lü kao xiang. Qi xuan yuan ji.”

Xuan here means completeness or thoroughness, implying a state where everything is fully balanced and aligned. The person in this line stands at the final stage of their journey, reflecting on their past actions. They scrutinize every decision, weighing its outcomes—good or bad—and ensuring that everything they have done is complete, without any regrets or mistakes. Once this is achieved, the person’s work is considered finished, and they have reached the highest level of success and virtue.

This line represents the culmination of a life of practice, where all actions have been taken with wisdom and consideration. The result is yuan ji—great good fortune, the outcome of a life lived in harmony with the dao. It signals the completion of a cycle, where everything falls into place and the individual attains a state of inner clarity anoutput:output:d balance.

Example:

Consider the life of Confucius. In his later years, Confucius reflected on his life and career, saying, “At fifteen, I set my heart on learning; at thirty, I was established; at forty, I was free from doubts; at fifty, I understood the will of heaven; at sixty, my ear was attuned to the truth; and at seventy, I could follow my heart’s desire without overstepping the bounds of propriety.” This quote encapsulates the growth of Confucius’s wisdom over his lifetime. By the time he was seventy, he had reached a stage where he could act freely, in full alignment with his values, and without violating the principles of propriety. His actions were in harmony with the world, and his understanding of life’s complexities was clear and unclouded. This final stage of life represents the peak of personal cultivation—when a person has not only mastered their inner self but also understands how to navigate the world smoothly and with ease.

Confucius’s journey illustrates the idea of shi lü kao xiang, or the complete reflection on one’s actions. By living according to his principles, Confucius reached the highest state of wisdom, where his every action was in perfect alignment with the world around him. This is the “complete and ultimate good fortune” mentioned in the text, as his life became a reflection of the ideal way to live.

Expanded Interpretation and Context:

These two lines in the I Ching provide profound insights into leadership, personal growth, and the development of wisdom over time.

The first line warns against the dangers of excessive self-confidence and arrogance. While those in power may possess the strength, wisdom, and authority to make decisions, they must always remain humble and receptive to the thoughts and concerns of others. Rulers or leaders who listen only to their own voices risk losing touch with reality and alienating those they are meant to serve. The story of Zhu Yuanzhang’s abolishment of the prime minister position is a poignant reminder of the risks associated with absolute power and the failure to heed the wisdom of others.

The second line, in contrast, illustrates the ideal progression of wisdom. As one grows older and accumulates experiences, they should gradually come into greater alignment with the dao—the natural order of things. Reflecting on one’s actions, understanding the consequences, and striving to live in harmony with both internal and external realities lead to a life of completeness. Confucius’s life exemplifies this ideal: as he aged, his wisdom deepened, and his actions became more effortless, reflecting a life fully attuned to the truth.

In modern terms, these lines suggest that true success is not about domination or force; rather, it is about balance, humility, and reflection. A leader, whether in business, government, or any other field, must remain open to learning and adapting, continually refining their actions and decisions. On a personal level, the journey toward wisdom involves constant reflection, humility, and a deepening understanding of both oneself and the world around them. When these elements are in harmony, success becomes inevitable, and life flows with ease and purpose.