I Ching Hexagrams:Shi Trigram

The term “Shi ䷆” refers to a group of soldiers or an army. The Shi Hexagram primarily conveys principles related to mobilizing troops and conducting military campaigns. It is composed of the Kan (Water) and Kun (Earth) trigrams.

From the perspective of the hexagram’s imagery, Kan symbolizes water, representing soldiers, while Kun symbolizes the earth, representing farmers. Water within the earth mirrors the ancient Chinese system where farmers and soldiers were integrated—a policy of drawing soldiers from farmers or training farmers as soldiers. The earth can contain and nourish water, just as farmers can serve as a source of manpower for an army.

In terms of the hexagram’s moral principles, the inner trigram Kan represents danger and traps, while the outer trigram Kun represents gentleness and compliance. This suggests addressing peril with a calm and strategic approach—concealing unpredictable actions within an outward appearance of peace and stillness. Such a balance is the essence of effective military strategy.

From the perspective of the six lines of the hexagram, only the second line (Nine in the Second Place) is a yang line, surrounded by yin lines. Positioned centrally in the lower trigram, it symbolizes a general leading an army into battle.

“Shi. Perseverance. The elder statesman brings good fortune. No blame.”

Here, “Perseverance” indicates righteousness and steadfastness. “Elder statesman” refers to an experienced and highly respected general, trusted and revered by the people. The foundation of military strategy lies in righteousness—fighting with a just cause, punishing wrongdoing, and aligning military actions with moral principles. As the Commentary on the Image states: “Though war exhausts the people and depletes resources, if the cause is just, the people will still willingly support it.”

In the Shi Hexagram, the fifth line (Six in the Fifth Place) represents the ruler, who aligns military campaigns with the will of Heaven and appoints capable generals (symbolized by Nine in the Second Place) to lead the army. With such righteous leadership, success and harmony are ensured.

Example Analysis: In ancient China, King Tang of Shang rose against the tyrant King Jie of Xia. His campaign was seen as just and aligned with the will of Heaven. People across the land rallied to his cause, and even those from distant regions eagerly awaited liberation. Although war brings suffering and disruption, a righteous war, aligned with the people’s will and moral principles, garners widespread support. This embodies the central theme of “Perseverance” in the Shi Hexagram.

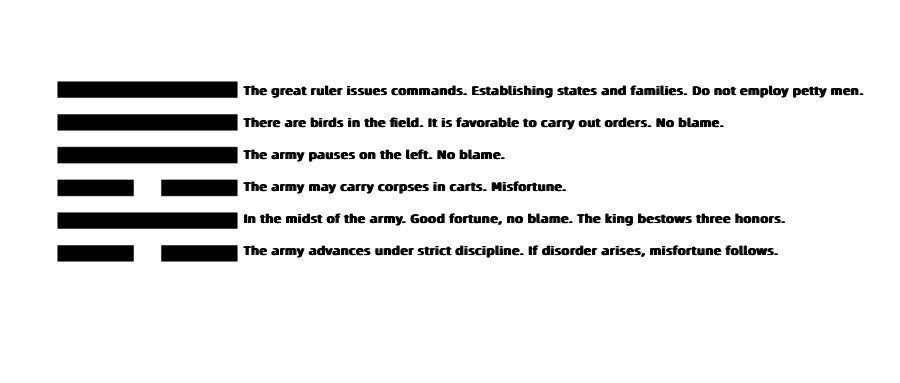

Initial Six: The army advances under strict discipline. If disorder arises, misfortune follows.

“Lü” originally referred to musical instruments used during military campaigns in ancient China. In those times, military operations were always accompanied by disciplined musical rhythms. When the music was harmonious, soldiers acted in unison, advancing and retreating in an orderly fashion. Conversely, if the music was chaotic, the formation would fall apart, and defeat would be inevitable. Over time, “Lü” came to symbolize military discipline and command regulations—the principles governing the deployment and actions of an army.

The Initial Six line represents the very beginning of a military campaign. If the campaign is launched to correct injustice, quell rebellion, and restore order, it aligns with the principles of righteous warfare. Furthermore, if strict discipline is maintained from the outset and orders are carried out without hesitation, it adheres to the essence of effective military operations.

“Bu Zang” refers to misfortune arising from poor conduct. If an army is mobilized without a just cause or if discipline is neglected, even victory would feel like defeat. Regardless of battlefield success, disregarding orders and military discipline will inevitably lead to disaster, as such actions violate the principles of responsible leadership.

Example Analysis:

During the Han Dynasty, General Li Guang (?-119 BCE) was renowned for his extraordinary courage and battlefield prowess. His fearless leadership earned him the admiration and loyalty of his soldiers. However, Li Guang often neglected military discipline and strategic formations. He frequently led small detachments deep into enemy territory, relying solely on bravery and sheer determination. Although he achieved several victories, his disregard for discipline and logistical planning often left his troops isolated and vulnerable, ultimately leading to catastrophic defeats. While his valor was admirable, his approach to military leadership was unsustainable and served as a cautionary lesson.

Nine in the Second Place: In the midst of the army. Good fortune, no blame. The king bestows three honors.

The Nine in the Second Place occupies the central position of the lower trigram, symbolizing strength and balance. As the key yang line surrounded by yin lines, it represents a general trusted by the ruler and followed by the troops. This line corresponds to the “elder statesman” mentioned in the hexagram’s main text, signifying a leader entrusted with supreme command over military affairs.

The general possesses both authority and integrity, allowing him to act decisively while maintaining respect for the ruler’s authority. However, if a general becomes arrogant and oversteps his bounds, he risks defying the principles of loyalty and propriety. Conversely, if a general hesitates and fails to act decisively, victory may slip away. Therefore, a general must strike a delicate balance between authority and humility to achieve success.

“The king bestows three honors” symbolizes the ruler’s deep trust and repeated rewards for the general’s competence and loyalty. It signifies the ruler’s reliance on this key military leader to ensure victory.

Example Analysis:

In the late Qing Dynasty, China faced a period of national decline and internal turmoil. Zeng Guofan (1811–1872) was repeatedly entrusted with critical military responsibilities by the imperial court. Despite being a Han Chinese official in a Manchu-ruled dynasty, Zeng earned the court’s trust through his disciplined leadership, repeated military successes, and steadfast adherence to principles of loyalty and integrity. His balanced approach to authority—neither overstepping his bounds nor shrinking from responsibility—earned him the posthumous title “Wenzheng” (Duke of Literary Integrity), the highest honor of moral and intellectual virtue.

Six in the Third Place: The army may carry corpses in carts. Misfortune.

“Yu” refers to a large war chariot. The Six in the Third Place is a yin line occupying a yang position, symbolizing a leader who lacks the strength and wisdom required for command. This represents a general who is reckless and overconfident, showing courage without strategy, and underestimating the enemy. As a result, his army suffers a crushing defeat, and the dead are carried back in carts—a grim and tragic outcome.

Example Analysis:

In the Battle of Fei River (383 CE), Fu Jian (338–385), ruler of the Former Qin dynasty, commanded an army of 800,000 soldiers. Confident in his overwhelming numbers and previous successes, he famously boasted that their whips alone could stop the river’s flow. However, his arrogance and underestimation of the Eastern Jin forces led to disaster. The Eastern Jin general Xie An executed a brilliant tactical retreat, tricking Fu Jian’s forces into chaos. Panic spread throughout the Qin army, and despite their numerical superiority, they were utterly defeated. Fu Jian’s recklessness serves as a timeless lesson in military humility and caution.

Six in the Fourth Place: The army pauses on the left. No blame.

“Left pause” refers to a strategic withdrawal or temporary halt in military operations. The Six in the Fourth Place is a yin line in a yin position, symbolizing a general who lacks overwhelming strength but understands his limits. Although not perfectly positioned, he acts appropriately by choosing to withdraw when victory is unattainable. This decision preserves the army’s strength and prevents unnecessary losses. However, if the general retreats when victory is within reach out of fear or indecision, it would be considered a grave mistake.

Example Analysis:

During the Northern and Southern Dynasties period, General Tan Daoji (?-436) of the Liu Song dynasty led an expedition against the Northern Wei. As his forces advanced deep into enemy territory, supply lines grew thin, and the troops faced severe food shortages. By the time they reached Licheng, provisions had completely run out. Tan Daoji employed clever deception to mislead the enemy and successfully withdrew his forces to safety. His ability to assess the situation, recognize his limits, and make a strategic retreat preserved his troops and demonstrated exceptional military wisdom.

Six in the Fifth Place: There are birds in the field. It is favorable to carry out orders. No blame. The eldest son leads the army, while the younger sons carry corpses. Divination shows misfortune.

“Carry out orders” refers to acting under the ruler’s command to suppress rebellion or defend the state. The Six in the Fifth Place is a yin line in a central position of the upper trigram, symbolizing a wise and righteous ruler who understands the principles of military engagement.

“Birds in the field” is a metaphor: if wild animals roam freely in the wilderness, they may be ignored. But if they enter the fields and damage crops, they must be hunted down. This symbolizes a just war—military action is justified only when provoked or necessary.

The “eldest son leads the army” refers to the capable general (represented by Nine in the Second Place), who leads the military campaign on behalf of the ruler. The “younger sons carrying corpses” refers to less competent commanders (symbolized by Six in the Third Place and Six in the Fourth Place), who lack the ability to lead. Entrusting them with military command invites disaster, even if the initial intention is righteous.

Example Analysis:

During the Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE), the early emperors adopted a policy of appeasement and tribute towards the Xiongnu, nomadic tribes from the north. However, these measures failed to prevent frequent raids and incursions. Under Emperor Wu of Han (156–87 BCE), the empire had grown strong enough to abandon appeasement. Following the principle of “birds in the field,” Emperor Wu launched a decisive military campaign against the Xiongnu. This not only secured the northern borders but also established control over the Silk Road, expanding Han influence across Central Asia.

Top Six: The great ruler issues commands. Establishing states and families. Do not employ petty men.

The Top Six line occupies the final position of the hexagram, representing the culmination of military efforts and the time to reward merit and secure stability. The “great ruler” refers to the sovereign who now grants titles and lands to those who have earned distinction in war.

“Establishing states” refers to granting noble titles and territories, while “establishing families” refers to appointing ministers and officials. However, the text warns against rewarding “petty men.” While they may have achieved victories or shown bravery in war, their lack of integrity and loyalty makes them unfit for positions of lasting authority. If petty men are entrusted with power, they may exploit the people, rebel against the state, and sow long-term chaos.

Example Analysis:

In the late Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), the central government began appointing military governors, such as Li Keyong (856–908) and Zhu Wen (852–912), to control vast regions. These men were granted enormous power and autonomy. However, their loyalty was questionable, and when the opportunity arose, they rebelled against the central authority. This fragmentation led to the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907–960 CE), marking the collapse of the Tang Dynasty. The warning in “do not employ petty men” serves as a timeless lesson for rulers in managing their generals and commanders wisely.

In the hustle and bustle of modern life, finding moments of balance, strength, and purpose can feel like a challenge. What if you could carry a piece of ancient wisdom with you, a reminder of resilience and strategy every step of the way?

This Taoist Eight Trigrams Tai Chi Brooch, inspired by the “Shi” Hexagram from the I Ching (Book of Changes), embodies timeless principles that resonate even in today’s fast-paced world.

A Symbol of Leadership and Strategy

The “Shi” Hexagram, central to this brooch’s design, represents mobilization and leadership. Its ancient roots lie in the art of warfare and the balance between action and preparation. The interplay of the Kan (Water) and Kun (Earth) trigrams teaches us this: life’s victories come from harmonizing strength with adaptability.

- Water, symbolizing soldiers, embodies fluidity and readiness.

- Earth, representing farmers, signifies stability and sustenance.

Together, they remind us that every great leader balances strategy with compassion, action with stillness.

A Modern Interpretation of Ancient Wisdom

Imagine this: you’re facing a difficult decision at work or home. The brooch, resting close to your heart, becomes a subtle reminder of the principles it symbolizes:

- Steadfastness: Stay true to your goals and values, no matter the challenges.

- Balance: Navigate life’s chaos with grace, blending bold moves with quiet resilience.

- Integrity: Lead with authenticity, knowing that true success is built on trust and justice.

A Story of Strength for the Ages

This brooch also carries the spirit of legendary leaders like King Tang of Shang, who united his people under a just cause, bringing hope and liberation. Similarly, it calls on us to pursue our own righteous paths, inspiring those around us.

In American culture, where individuality and leadership are celebrated, this brooch bridges the gap between ancient philosophy and modern aspirations. It’s a token for those who lead by example, act with purpose, and strive for harmony in their lives.

Crafted for the Modern Leader

Handcrafted with meticulous detail, this brooch is more than a fashion statement. It’s a conversation starter, a reflection of your inner strength, and a piece of history reimagined for today.

Why You’ll Love It

- A unique blend of elegance and symbolism.

- A perfect gift for leaders, visionaries, and anyone seeking balance in their journey.

- A wearable piece of ancient Chinese philosophy that aligns with modern values.

Carry Your Story Forward

The Taoist Eight Trigrams Tai Chi Brooch is more than an accessory—it’s a symbol of who you are and who you aspire to be.

Wear it to a business meeting, a casual outing, or even a moment of reflection at home. Let its energy remind you of the strength, strategy, and perseverance needed to conquer life’s battles.

Are you ready to embrace this timeless wisdom?

👉 Get yours today and wear the balance of the universe close to your heart.