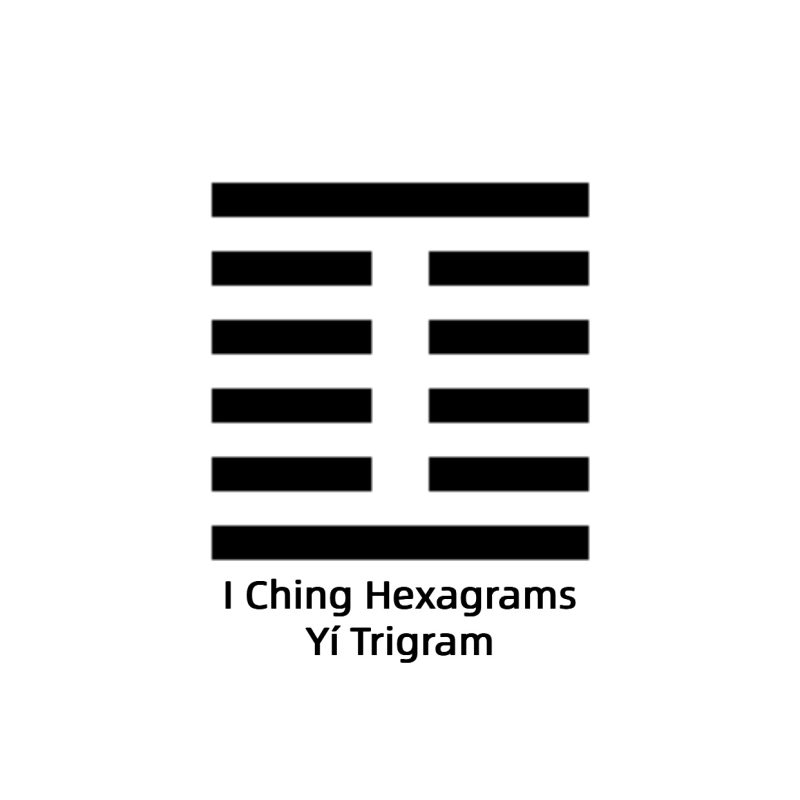

I Ching Hexagrams:Yí Trigram

The term “Yi” (颐) signifies nourishment or nurturing. The Yi hexagram is composed of the Zhen (震) and Gen (艮) trigrams. From the perspective of its line structure, it features two solid (yang) lines at the top and bottom, with four broken (yin) lines in the middle. The solid lines symbolize fullness, while the broken lines represent emptiness. This configuration resembles two rows of teeth with an empty space in between, forming the image of a nourished mouth.

From the perspective of hexagram virtues, the lower trigram, Zhen, symbolizes activity, while the upper trigram, Gen, represents stillness. This mirrors the act of chewing: the lower jaw moves while the upper jaw remains stationary. The Yi hexagram discusses nurturing, starting with the physical nourishment of the body and extending to the cultivation of virtue. It progresses from self-nurturing to nurturing others.

Yi. Perseverance brings good fortune. Observe how nourishment is sought. Seek sustenance for oneself.

Nurturing must follow the path of righteousness to achieve good fortune. Just as Heaven and Earth nurture all things with precision and harmony, humans must adhere to righteousness in both self-nurturing and nurturing others. The phrase “Observe how nourishment is sought” suggests examining whether one’s approach to self-care and sustenance aligns with moral principles. The philosophy of nourishment emphasizes prioritizing the public good when nurturing others and focusing on virtue cultivation when nurturing oneself, with physical sustenance being secondary.

In the hexagram lines, the solid (yang) lines symbolize substantial virtue, enabling one to both nurture oneself and others. The broken (yin) lines, however, represent dependency on others for sustenance. The lower trigram’s three lines belong to Zhen, which signifies movement. This symbolizes excessive eating and greed, leading to misfortune. In contrast, the upper trigram’s three lines belong to Gen, which signifies stillness. This represents moderation in diet and an emphasis on cultivating virtue, leading to good fortune.

Illustrative Explanation: Mencius once said: “The body has both greater and lesser parts, noble and base elements. Do not let the lesser harm the greater, or the base harm the noble. Those who nurture the lesser are small-minded, while those who nurture the greater are virtuous.” Here, “lesser” or “base” refers to the body’s senses, which are easily influenced by external temptations and constraints. “Greater” or “noble” refers to virtue and wisdom, which require continuous self-reflection and cultivation. By contrasting “lesser” with “greater” and “base” with “noble,” Mencius emphasizes that what elevates humans above all other beings is their capacity for rational thought. Passively, this allows them to transcend worldly desires, such as laziness or the pursuit of pleasure and avoidance of hardship. Actively, it enables them to fulfill the demands of pure reason. Thus, the more a person exercises free will and autonomy in their decisions, the closer they align with the righteous path of nourishment and become a truly “great individual.”

Line 1 (Initial Nine):

“Abandon your spiritual turtle; observe my greedy appetite. Misfortune.”

The word “you” refers to the second person, in this case, the first line (初九). “I” refers to the ninth line at the top (上九). “Greedy appetite” (朵颐) implies excessive craving or indulgence. In this context, the spiritual turtle symbolizes self-sufficiency, as the mythical turtle is believed to survive without external sustenance and live a long life.

The first line is a strong (yang) line in a yang position, meaning it has the potential to sustain itself without depending on others. However, due to its active nature (as it is part of the Zhen trigram, which represents movement), the first line seeks nourishment from the ninth line at the top, which symbolizes a nurturing figure. Thus, the text says, “Abandon your spiritual turtle; observe my greedy appetite.” This means that instead of cherishing its self-sustaining nature, the first line forsakes this advantage and greedily seeks sustenance from others, leading to misfortune.

Illustration:

The saying “Heaven has bestowed talent upon me for a purpose” reflects that everyone has unique talents and abilities. By recognizing and wisely utilizing these strengths, anyone can achieve a bright future. As the old adage says, “Every profession can produce a master.” When choosing a career or life path, one must consider their passions, potential, and interests. However, blindly following trends, envying others’ achievements, or succumbing to short-term gains without a clear goal will lead to a directionless life. “Abandon your spiritual turtle; observe my greedy appetite” serves as a reminder to be content and cherish one’s unique strengths.

Line 2

(Six in the Second Position):

“Reversed nourishment; defying principles. Seeking sustenance on the hilltop leads to misfortune.”

The term “reversed” (颠) implies a distortion or reversal of proper order. “Defying” (拂) means acting against established norms or principles. “Principles” (经) refers to the natural order and moral principles. “Hilltop” (丘) symbolizes a small hill outside the city, reflecting the imagery of the upper trigram Gen (艮), which represents a mountain.

The second line is a soft (yin) line in a yin position, indicating weakness and reliance on external support. Properly, it should remain steadfast and wait for assistance from the fifth line (六五), representing a ruler who provides nourishment. However, if the second line seeks sustenance from the first line (初九), it disrupts the proper order of nourishment, as traditionally, those in higher positions provide for those below them. Seeking sustenance from below is a reversal of this principle, leading to misfortune.

Additionally, the second line has no direct correspondence with the ninth line at the top. If it rashly seeks sustenance from the top line, this would reflect impulsiveness and violation of moral principles, leading to misfortune. Thus, the text warns, “Reversed nourishment; defying principles. Seeking sustenance on the hilltop leads to misfortune.”

Illustration:

After the Mongols conquered China, they implemented an inequitable social hierarchy. The royalty, nobility, military, and clergy occupied privileged positions, exploiting the common people while neglecting governance and failing to empathize with the populace. Those in power sought wealth and sustenance from the lower classes, violating the principle that higher positions should nurture and care for those below. This “reversed nourishment” led to widespread unrest and, ultimately, the fall of their empire.

Line 3

“Disorder in Nourishment.” Misfortune. Not appropriate for use for ten years. No benefit.

The term “zhēn” here is not explained as “upright” but rather as “adverse and conflicting.” It emphasizes that one side in an opposition always prevails while the other fails, as further detailed in the explanation of Hexagram 17, Line 4. Line 3, although corresponding with Line 6 above, and capable of receiving its support, is represented by a yin (weak) line occupying a yang (strong) position. This signifies imbalance and an inability to adhere to proper principles. Furthermore, its position is not central, making it incapable of practicing moderation. Coupled with its placement at the uppermost part of the lower trigram, Zhen (Movement), it suggests constant restlessness. When one moves without following the correct path and seeks nourishment through unscrupulous means, it violates the principle of “nourishment” (Yi), leading to misfortune despite the proper correspondence. The phrase “ten years not used” implies permanent inutility and a lack of benefit.

Example Interpretation:

During the Northern and Southern Dynasties, Yan Zhitui (531–?) authored a book titled Yan Family Instructions. In the chapter Teaching Children, he recounts a story: Among the aristocracy of Northern Qi, many were of Xianbei descent. A scholar-official taught his children to speak the Xianbei language and play the pipa, hoping to win favor with nobles. Yan Zhitui warned his descendants against this approach, stating that even if it led to high rank, it was not worth pursuing. Yan Zhitui understood the principle that “flattering words and insincere expressions seldom accompany true virtue” and refused to seek wealth through improper means. His actions reflect the wisdom of adhering to the idea of “disorder in nourishment,” avoiding misfortune by rejecting unethical paths.

Line 4

“Inverted Nourishment.” Favorable. A tiger glares intently, its desire relentless. No fault.

The phrase “desire relentless” refers to persistence and unceasing effort. Line 4 has entered the upper trigram, Gen (Stillness), focusing on cultivating virtue. Represented by a yin (weak) line in a yin position, Line 4 symbolizes a high-ranking minister whose personal abilities are insufficient for self-sustenance. However, being properly positioned and corresponding with the strong Line 1 below, it can seek support from Line 1. Normally, those in higher positions provide nourishment to those below. When Line 4, in an upper position, seeks assistance from the lower Line 1, it reverses this proper order, leading to the description of “inverted nourishment.”

Nonetheless, Line 4 humbles itself to request aid from Line 1, thereby enabling the virtuous Line 1 to fulfill its potential for benefiting society. This cooperation leads to the practice of benevolent governance, bringing peace and prosperity to the people. Hence, it is deemed favorable.

Additionally, animals like turtles are self-sufficient, while tigers are highly reliant on external sources for nourishment. The imagery of a tiger “glaring intently, its desire relentless” symbolizes that Line 4 must cultivate an imposing and dignified demeanor, akin to a tiger strategizing its hunt. Its persistence in seeking aid from Line 1 guarantees a steady supply of support. This analogy represents Line 4’s unwavering determination to enlist the aid of capable individuals like Line 1. By combining dignity and persistence, Line 4 aligns with the principle of higher-ranking individuals seeking nourishment from those below, thus avoiding any fault.

Example Interpretation:

In the Northern Song Dynasty, Chancellor Lü Mengzheng (946–1011) once asked his son about public opinion regarding his administration. His son responded that while his achievements were well-regarded, some criticized him as being ineffectual, with much of his authority delegated to others. Lü Mengzheng replied, “I may indeed lack personal ability, but I excel at employing capable individuals, and that is the essence of being a chancellor.” Lü Mengzheng carried a small notebook listing talented individuals he had personally sought out. Many of the empire’s most valued officials were discovered through this record. His determination and strategy reflect the spirit of “a tiger glares intently, its desire relentless,” perfectly embodying the wisdom of Hexagram 27, Line 4.

Line 5

“Defying the Norms.” Remaining steadfast brings good fortune. Do not cross great rivers.

Line 5 is a yielding line, symbolizing a ruler who is gentle and lacks the strength to sustain the entire nation. However, being closely associated with Line 6 (the superior sage), it signifies that the ruler relies on the wisdom and support of a virtuous advisor to achieve his goals of governing and benefiting the people. This dependence on an advisor contradicts the conventional principle that an emperor should nourish his people, hence the phrase “defying the norms.” However, if the ruler can remain steadfast in the right path, trust the sage without doubt, and govern with benevolence, good fortune will follow—hence “remaining steadfast brings good fortune.”

Nevertheless, the ruler’s inherent weakness means that while he may rely on capable advisors during peaceful times, he lacks the strength to navigate crises or overcome major challenges. Thus, the line warns, “Do not cross great rivers,” implying that he should avoid undertaking overly ambitious ventures beyond his capabilities.

Example Interpretation:

After the fall of the Western Jin Dynasty, Sima Rui (276–322) ascended the throne in Jiankang, becoming the founding emperor of the Eastern Jin Dynasty. At that time, his authority was not firmly established, and the political situation remained unstable. Sima Rui had to “defy the norms” by relying heavily on Wang Dao, leading to the famous saying, “Wang and Sima rule the world together.” This dependence helped pacify the people of the southern regions and solidify the foundation of the Eastern Jin Dynasty. However, the long-standing political complacency and corruption were difficult to eradicate, and reclaiming the Central Plains was beyond Sima Rui’s abilities. Just as the line states, “Do not cross great rivers,” he had no choice but to maintain a precarious existence in the south.

Line 6

“Relying on Nourishment.” Caution leads to good fortune. Favorable to cross great rivers.

Line 5’s reliance on Line 6 for nourishment implies that the governance of the nation depends on the virtue and capability of the advisor, which is the meaning of “relying on nourishment.” As a minister entrusted with the weighty responsibility of sustaining the realm, he must maintain a sense of caution and vigilance—acting with diligence and prudence, as if walking on thin ice or standing on the edge of an abyss. This cautious approach ensures success and good fortune, hence “caution leads to good fortune.”

Since the ruler has placed full trust in the minister, he should devote himself wholeheartedly to serving the people and restoring order to the nation. This commitment and effort make it “favorable to cross great rivers,” suggesting that with the right leadership, even major challenges can be overcome.

Example Interpretation:

As previously mentioned, Wang Dao (276–339) played a crucial role in establishing the Eastern Jin Dynasty. He successfully integrated the aristocratic families migrating from the north with the influential local clans in the south, fostering unity and ensuring political stability. His efforts earned him the reputation of being the “Yiwu of Jiangzuo” (comparing him to the famous statesman Guan Zhong of the Spring and Autumn period).

However, Wang Dao’s brother, Wang Dun, failed to understand the principle of “relying on nourishment with caution.” Instead, he abused the family’s influence, acting arrogantly and even leading a rebellion against the court. His reckless ambition ultimately led to his defeat and death in disgrace, serving as a cautionary tale against neglecting the responsibilities that come with power.