I Ching:Kun Hexagram(䷁)

Kun represents the Earth, signifying alignment with the natural order (“Heaven’s Way”) through humility and virtue, bearing the weight of all things. The single hexagram Kun consists of three yin lines, symbolizing the condensed form of yin energy, with the Earth being its ultimate manifestation. The doubled Kun hexagram is formed by stacking two single Kun hexagrams, symbolizing the Earth’s expansive and unending terrain, with its elevation higher in the north and lower in the south.

From the perspective of its attributes, Kun signifies submissiveness and adaptability. As a symbol, Kun can represent a mother or a subordinate.

The Judgment for Kun reads:

“Kun. Supreme success. Favorable for the mare’s purity.

The noble person moves forward.

First disoriented, then finds their master.

Favorable in the southwest to gain allies,

Unfavorable in the northeast, where allies are lost.

Steadfast brings fortune.”

The “mare” symbolizes the feminine principle. According to the fifth chapter of the “Explaining the Hexagrams” commentary, yin hexagrams correspond to the western and southern directions (Dui in the west, Kun in the southwest, and Li in the south), while yang hexagrams correspond to the eastern and northern directions (Zhen in the east, Gen in the northeast, Kan in the north, and Qian in the northwest).

The “southwest” metaphorically represents the path of yin’s submissive flexibility, while the “northeast” symbolizes the path of yang’s resolute strength. “Allies” here refer to companions or counterparts; yin aligns with yang as its natural counterpart.

Kun stands opposite to Qian, the hexagram of pure yang. Comprised solely of yin lines, Kun represents complete receptivity and gentleness, embodying profound principles of openness and universal connection. While no creature matches the dragon’s ability to soar through the skies, none rivals the horse’s ability to traverse the Earth. The “mare” metaphor in the Judgment encapsulates this dual nature: “mare” symbolizes gentleness, while “horse” signifies endurance and strength.

Gentleness (the “origin”) and endurance (the “success”) combine to define Kun’s virtue of steadfastness. While gentleness alone is insufficient for enduring progress, the mare—gentle yet capable of great distances—can bear the burden of long journeys. Thus, the text states: “The noble person moves forward.”

Being a pure yin hexagram, Kun teaches the value of recognizing one’s limitations. Without the ability to take the lead, it advises waiting for guidance and following others’ initiatives. Striving to stand out prematurely leads to losing direction; only by maintaining gentleness and receptivity can one gain the leadership of the resolute Qian. Hence, the Judgment advises: “First disoriented, then finds their master.”

A subordinate must embody Kun’s gentleness to gain the trust and support of peers (“southwest to gain allies”). Conversely, adopting Qian’s dominant approach as a subordinate disrupts harmony (“northeast loses allies”). In essence, Kun’s principle is to lead with gentleness and follow with strength. By steadfastly adhering to this principle, success and fortune are assured.

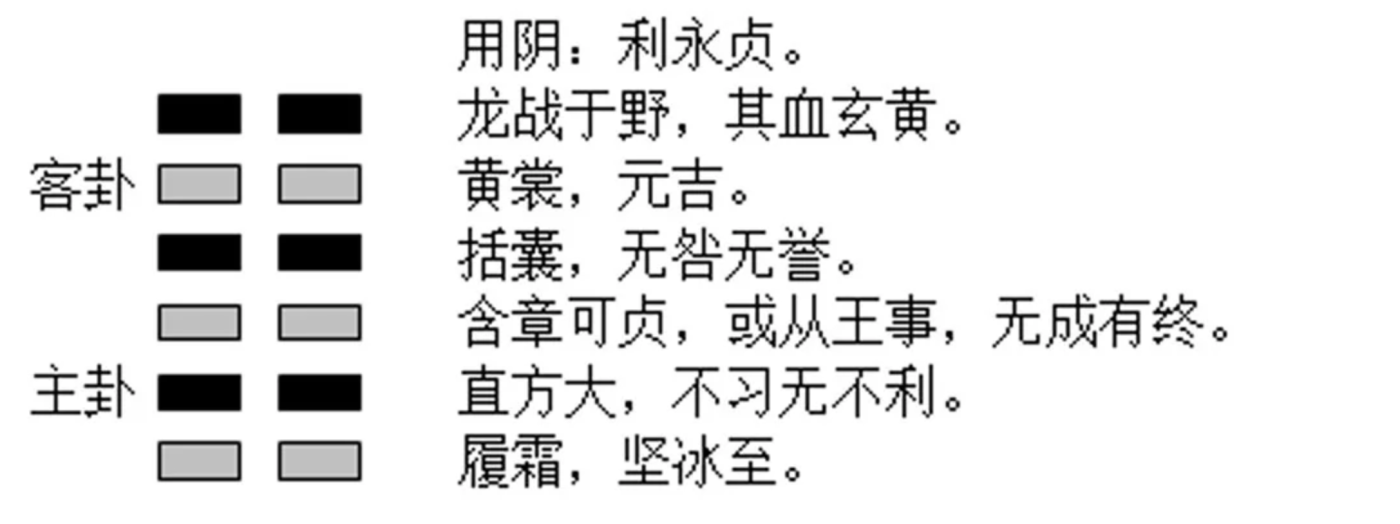

Line 1 (Initial Six):

“Step on frost, and solid ice will follow.”

The “Six” represents a yin line. In this position, the yin line occupies a yang place, symbolizing the initial rise of yin energy. At this stage, it is still weak, manifesting as frost. By observing frost underfoot, one can foresee the eventual formation of solid, thicker layers of ice as yin energy strengthens.

Example Explanation:

As the saying goes, “Three feet of ice does not form in a single day.” The emergence of any phenomenon has early signs. For instance, noticing a sudden increase in ants moving their nests might indicate imminent rain, or observing animals acting restlessly could signal an approaching earthquake. This reflects the principle of “Step on frost, and solid ice will follow.”

Line 2 (Six in the Second Position):

“Straight, square, and great.

Practice is unnecessary; all will be favorable.”

In this position, the yin line occupies a yin place, situated in the middle of the lower trigram. Being appropriately positioned, it represents the core essence of Kun. Among the other five lines in Kun:

- The Initial Six marks the early stage of yin energy, still weak.

- The Top Six indicates excessive yin, which opposes yang.

- The Third Six occupies a yang position, resulting in imbalance.

- The Fourth Six is correct in position but lacks central alignment.

- The Fifth Six, while central, is improperly positioned in a yang place.

Only the Second Six, as a yin line in a yin place, achieves proper balance and embodies the core virtues of Kun.

Ancient thinkers described the heavens as round and constantly moving, while the Earth was seen as square and stationary. Qian (the hexagram of Heaven) embodies “greatness” and “straightness,” with the “Explaining the Hexagrams” commentary praising its active, direct motion. Kun (the hexagram of Earth) embodies “squareness,” with the commentary extolling its ultimate tranquility and upright virtue.

The Second Six uniquely captures Kun’s essence, with the commentary emphasizing “straight,” “square,” and “great.” Squareness depends on straightness as its foundation and aims for greatness as its ultimate goal. Just as upright actions require an honest heart, they also lead to the cultivation of grand virtues and achievements.

Kun’s virtue relies on aligning with Qian’s principles. Kun’s gentleness harmonizes with Qian’s direct motion, thus becoming “straight.” Qian, as the sky, covers all beneath it; Kun, as the Earth, supports all above it. In this relationship, Kun complements Qian’s greatness. Therefore, it is through “straightness” that Kun achieves “squareness,” and through “squareness” that it attains “greatness.” Similarly, a sincere and upright spirit guides correct actions, which in turn shape noble and expansive character. By adhering to the natural order, where yin supports yang, success comes effortlessly.

Example Explanation:

In the early Western Han dynasty, Cao Shen (?-190 BCE) succeeded Xiao He as chancellor. Cao followed Xiao’s policies to the letter, implementing them without any deviation. History refers to this as “Xiao’s rules, Cao’s governance.”

Cao Shen’s strict adherence to Xiao’s framework exemplified Kun’s principle of “straightness” — faithfully upholding established standards without deviation. This, in turn, demonstrated Kun’s “squareness” — a tranquil, steadfast approach marked by fairness and leniency toward the people. As a result, he achieved “greatness,” fostering societal prosperity and strengthening the nation.

Cao Shen’s “hands-off” governance earned widespread praise because Xiao He’s laws were sound and effective. This illustrates that by adhering to correct principles, one can achieve favorable outcomes.

Line 3 (Six in the Third Position):

“Conceal brilliance, uphold integrity.

Follow the ruler’s orders.

Claim no credit, but ensure completion.”

The phrase “claim no credit” emphasizes humility—refusing to take personal pride in accomplishments. Positioned at the top of the lower trigram, the Six in the Third Position represents a minister who has gained a suitable role. This line symbolizes a subordinate who embodies humility and restraint, patiently awaiting the ruler’s orders before acting and following the law in all endeavors.

By adhering firmly to these principles, one avoids misfortune or regret. The minister neither takes initiative independently nor seeks personal glory. When success is achieved, the credit is attributed to the ruler, with the minister regarding the outcome as merely fulfilling their duty. Their efforts are simply a loyal execution of the ruler’s commands.

Example:

General Guo Ziyi (697–781) of the Tang dynasty exemplified these qualities. He quelled the An-Shi Rebellion, repelled foreign invasions, and dedicated his life to safeguarding the Tang dynasty. Despite commanding hundreds of thousands of elite troops, Guo remained humble and loyal.

When the emperor relieved him of military power, he showed no resentment. When assigned minor administrative roles, he accepted them cheerfully. When conflict arose again, he returned to lead with the same diligence and dedication. After his death, Emperor Dezong praised him as “great in achievements, yet humble; elevated in rank, yet composed.”

Guo’s life of military service and humility embodied the ideal of “Conceal brilliance, uphold integrity. Follow the ruler’s orders. Claim no credit, but ensure completion.” His greatness lay in his steadfast modesty, a rare and inspiring example.

Line 4 (Six in the Fourth Position):

“Tie the bag.

No blame, no praise.”

The term “tie the bag” refers to securing the opening of a pouch, symbolizing cautious and meticulous behavior. Among the six positions in a hexagram, the fourth is adjacent to the fifth—the ruler’s position—making it a precarious and sensitive place.

As a yin line in a yin position, the Six in the Fourth Position advises ministers to maintain discretion, concealing their virtues and talents. By acting with such caution—like tying a bag to prevent contents from spilling—they avoid arousing suspicion or jealousy. Though this approach may not earn widespread recognition, it ensures the absence of disaster.

Example:

Prime Minister Lü Buwei (?–235 BCE) of the Qin dynasty serves as a counterexample. As a key figure who helped Qin Shi Huang ascend to power, Lü wielded immense authority but failed to practice restraint. His overreach, arrogance, and lack of humility eventually provoked the emperor’s suspicion. Exiled and disgraced, Lü ultimately died by suicide.

Had Lü “tied the bag” by tempering his ambitions and exercising caution, he might have avoided his tragic downfall. This story illustrates the importance of humility and discretion for those in positions of power.

Line 5 (Six in the Fifth Position):

“Yellow robe. Supreme good fortune.”

The color yellow represents balance and neutrality in Chinese tradition. In the five elements (Wu Xing), yellow corresponds to the earth element, which occupies the central position. In ancient China, “robe” referred to garments worn on the lower body, symbolizing humility and submission.

The phrase “yellow robe” here signifies a leader or minister who, despite their high status, remains modest and grounded. Positioned at the middle of the upper trigram, this line embodies virtue through balance and gentleness. A minister, even at the pinnacle of power, must adhere to humility and fairness, harmonizing strength with softness to achieve great success and blessings.

Example:

Wang Dao (276–339), a prominent statesman of the Eastern Jin dynasty, played a critical role in stabilizing the court during a tumultuous era. Though his family was wealthy and influential, Wang Dao remained humble and loyal to the Jin court. His composure and dedication ensured his reinstatement even after being implicated in his cousin Wang Dun’s rebellion. His ability to govern effectively while staying humble earned widespread recognition and trust.

Line 6 (Top Position):

“The dragon battles in the wilderness.

Its blood is black and yellow.”

In the Qian Hexagram, the dragon symbolizes strength and virtue. However, when this imagery appears in the topmost line of the Kun Hexagram, it warns of excess. Here, the metaphor reflects an imbalance where yin energy (Kun) grows overly dominant and clashes with yang energy (Qian).

The term “wilderness” represents the outermost, unchecked regions. When yin defies its inherent nature of submission and opposes yang, conflict ensues. The resulting battle leaves both forces weakened—symbolized by blood in “black and yellow,” representing the heavens (black) and the earth (yellow). This imagery serves as a cautionary tale against excess and rebellion, advocating for the balance and harmony between opposing forces.

Example:

During the late Eastern Han dynasty, power struggles between the imperial family’s maternal relatives (the “Outer Court”) and court eunuchs led to political chaos. Empress dowagers often dominated the court when emperors ascended the throne as children. Once grown, these emperors retaliated against overreaching relatives by enlisting eunuchs to eliminate them. This vicious cycle of conflict—”the dragon battles in the wilderness”—weakened the Han dynasty, leading to its eventual collapse.Finding Harmony Amid Chaos

Jennifer had always been fascinated by philosophy. One evening, she was reading about the I Ching and the balance of Yin and Yang discussed in ancient Chinese wisdom. The idea that strength comes from accepting both light and dark resonated deeply with her chaotic life—a demanding job, constant stress, and a feeling of being unmoored.

As she reflected, she remembered a recent conversation about “Line 3 (Six in the Third Position)”—the idea of embodying grace and quiet strength. Inspired, she decided to find something tangible to remind her daily of this balance. That’s when she found the 18K Gold Plated Tai Chi Yin Yang Pendant Necklace.

The necklace wasn’t just jewelry to her; it became a token of her journey toward inner peace. Every time she touched it, she was reminded to breathe, to embrace life’s dualities, and to find her center. Jennifer’s colleagues started noticing a change—she seemed calmer, more grounded. And she knew this wasn’t just about the necklace; it was about embracing its message.

For Jennifer, the necklace wasn’t an accessory—it was a philosophy she carried with her every day.

Strength Through Balance

During a college philosophy class, Mark was introduced to the concept of Yin and Yang. The professor explained, “True strength comes from harmony—when opposing forces coexist and complement each other.” The words struck a chord, but it wasn’t until years later, after navigating a difficult divorce and career change, that Mark truly understood their meaning.

Mark stumbled upon an article about “Line 6 (Top Position)”—a tale of opposing forces clashing unnecessarily, leading to mutual loss. It reminded him of his own struggles, fighting battles that only drained him. Determined to change, he sought a symbol of this new understanding. He discovered the Chinese Dragon Yin Yang Tai Chi Pendant Necklace, with its intricate dragon design guarding the balance of Yin and Yang.

Wearing it daily, Mark felt a renewed sense of purpose. He no longer fought every challenge head-on; instead, he approached life with balance and clarity. Friends marveled at his transformation, often asking, “What’s your secret?” Mark would simply smile, touch the pendant, and say, “It reminds me to stay balanced, no matter what.”