Na Yin: Chinese Divination & Elements

What is “Na Yin”?

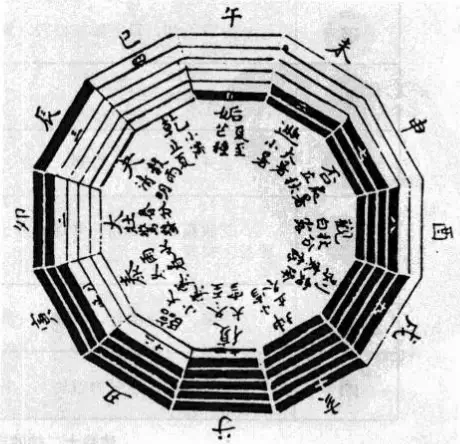

“Na Yin” refers to a method widely employed in the divinatory arts—especially within the numerological aspects of the I Ching—wherein numerical values are elucidated through the elemental attributes of musical scales. In this context, the term “Yin” (sound) denotes the ancient Chinese practice of synthesizing the sixty‐term sexagenary cycle (Jiazi), the five fundamental musical tones, and the twelve pitch scales based on the intrinsic qualities of various musical modes.This intricate system of Na Yin, with its connections to the elements and musical tones, has also inspired modern creations such as yin yang jewelry, which seeks to embody the balance and harmony that is central to these ancient concepts. These five tones—Gong, Shang, Jue, Zhi, and Yu—correspond respectively to the numbers 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6 (analogous to the modern solfège syllables Do, Re, Mi, So, La). The term “Na” implies “to incorporate” or “to admit,” so “Na Yin” essentially means integrating musical scales into the Yin–Yang and Five Elements (Wu Xing) system. Within this framework, each musical tone is paired with an element: Gong with Earth, Shang with Metal, Jue with Wood, Zhi with Fire, and Yu with Water.

The Origins of the “Na Yin” Doctrine

The theory of Na Yin originates from Dong Zhongshu’s arrangement of the Five Elements as well as the “Five Elements” doctrine expounded in the Hong Fan. This concept forms a cornerstone of ancient Chinese metaphysical numerology and also constitutes an integral component of traditional Chinese medicine’s theory of vital energy. In essence, Na Yin represents the ancients’ inquiry into the relationship between sound and human affairs—a manifestation of their profound desire to comprehend the workings of the universe.

Derivation of Na Yin Through the Five Elements

How is Na Yin deduced from the Five Elements? In the Yin–Yang system, the fundamental constituents are the Five Elements—Metal, Wood, Water, Fire, and Earth. Each of these elements can be calculated according to specific numerical values, which in turn are derived from the He Tu diagram. As recorded in the Kao Yuan, “The total of the Great Expansion is fifty, though its operative value is forty-nine. By subtracting the sum of the two Heavenly Stems and the two Earthly Branches (when totaled within forty-nine) and then removing multiples of ten, the remainders—namely, 16 for Water, 27 for Fire, 38 for Wood, 49 for Metal, and 50 for Earth—are assigned to their respective elements for Na Yin.”

For example, consider the pair Jiazi and Yichou. In this case, Jia is assigned the value nine and Zi likewise nine; similarly, Yi and Chou are both valued at eight. Their total sum is thirty-four. Subtracting this from forty-nine yields fifteen; after eliminating the ten, the remainder is five. The number five corresponds to the Gong tone among the five musical notes, whose elemental attribute is Earth—and Earth, in traditional Chinese cosmology, gives rise to Metal. Thus, the Na Yin associated with Jiazi and Yichou is ascribed to the element Metal.

Matching Na Yin with the Sixty Jiazi

How is Na Yin aligned with the sixty Jiazi (sexagenary cycle)? The ten Heavenly Stems and the twelve Earthly Branches are paired in a fixed sequential order to produce sixty combinations—from Jiazi to Guihai—collectively known as the sixty Jiazi. The following is a list of these Na Yin pairings:

- Jiazi and Yichou – corresponding to “Sea Metal.”

- Bingyin and Dingmao – corresponding to “Furnace Fire.”

- Wuchen and Yisi – corresponding to “Great Forest Wood.”

- Gengwu and Xinwei – corresponding to “Roadside Earth.”

- Renshen and Guiyou – corresponding to “Sword-Edge Metal.”

- Jiaxu and Yihai – corresponding to “Mountain-top Fire.”

- Bingzi and Dingchou – corresponding to “Cave-bottom Water.”

- Wuyin and Yimao – corresponding to “City Wall Earth.”

- Gengchen and Xinsi – corresponding to “White Wax Metal.”

- Renwu and Guiwei – corresponding to “Willow Wood.”

- Jiashen and Yiyou – corresponding to “Spring Water.”

- Bingxu and Dinghai – corresponding to “Roof Earth.”

- Wuzi and Jichou – corresponding to “Thunderbolt Fire.”

- Gengyin and Xinmao – corresponding to “Pine–Cypress Wood.”

- Renchen and Guisi – corresponding to “Ever-Flowing Water.”

- Jiawu and Yiwei – corresponding to “Sand Metal.”

- Bingshen and Dingyou – corresponding to “Mountain-bottom Fire.”

- Wuxu and Yihai – corresponding to “Plain Wood.”

- Gengzi and Xinchou – corresponding to “Wall Earth.”

- Renyin and Guimao – corresponding to “Gold Foil Metal.”

- Jiachen and Yichou – corresponding to “Buddha Lamp Fire.”

- Bingchen and Dingsi – corresponding to “Heavenly River Water.”

- Wuwu and Jiyou – corresponding to “Great Station Earth.”

- Gengxu and Xinhai – corresponding to “Hairpin Gold.”

- Renzi and Guichou – corresponding to “Mulberry–Pine Wood.”

- Jiayin and Yimao – corresponding to “Great Creek Water.”

The Formation of the Twelve “Chen”

How were the twelve “Chen” (辰) established? Originally, the term “Chen” denoted the point of convergence between the sun and the moon. In the context of the traditional (lunar) calendar, the twelve Chen refer to the positions occupied by the sun during the waxing phases of the twelve months. The ancient Chinese divided the celestial ecliptic—a full circuit near the zodiac—into twelve equal segments and assigned the twelve Earthly Branches (Zi, Chou, Yin, Mao, Chen, Si, Wu, Wei, Shen, You, Xu, Hai) in order from west to east; intriguingly, this order is the reverse of the natural sequence. As recorded in the Zuo Zhuan (“Duke Zhao’s Seventh Year”), “the convergence of the sun and moon is called Chen.” Thus, the naming of the twelve Chen follows the sequence of the Earthly Branches. In antiquity, the twelve Chen served several key purposes:

- Chronological Recording:

The ancients used the twelve Chen to denote years, months, days, and even hours. For instance, the Rites of Zhou (Spring Officials, Feng Xiang Shi) records: “There are twelve years, twelve months, twelve Chen, ten days, and twenty-eight stellar positions—employed to sequence events in accordance with the celestial order.” As Jia Gongyan’s annotations clarify, these twelve Chen correspond to the sequence beginning with Zi, Chou, Yin, Mao, etc. The Guoyu (Chu Dialogues, Volume II) further notes that the ritual sacrifices of the ancient kings were arranged by incorporating one pure element, two refined ones, three sacrifices, four seasons, five colors, six tones, seven affairs, eight types, nine offerings, ten days, and twelve Chen. - Astronomical Sequencing:

The twelve Chen were also used to organize the positions of the stars. The Records of the Grand Historian (The Heavenly Officials) states, “The Big Dipper and its associated positions have been in use since time immemorial.” The Tang dynasty scholar Zhang Shoujie remarked that “the North Star establishes the twelve Chen, corresponding to the twelve provinces and the twenty-eight lunar mansions; this system has been employed since ancient times.” Similarly, Shen Kuo in the Song dynasty work Mengxi Bitan explains that the twelve Chen, extending from Zi and Chou to Xu and Hai, derive their names from the initial positions of celestial phenomena as described in the Zuo Zhuan. - Association with the Zodiac:

The twelve Chen were also paired with the twelve zodiac animals. The Han dynasty scholar Cai Yong, in his Yueling Q&A, observed that in the distribution of fowl over the five daily periods corresponding to the twelve Chen, only those animals domesticated by the household—specifically, the ox of Chou, the sheep of Wei, the dog of Xu, the rooster of You, and the pig of Hai—were consumed; any creatures of a lower status than the tiger were not used.

The Twelve Jian–Chu Deities: Their Significance

What, then, are the meanings of the Twelve Jian–Chu Deities? These deities comprise the following: Jian (Establishment), Chu (Elimination), Man (Fulfillment), Ping (Equilibrium), Ding (Stabilization), Zhi (Upholding), Po (Breakage), Wei (Peril), Cheng (Achievement), Shou (Collection), Kai (Opening), and Bi (Closure). Each is paired with one of the twelve Earthly Branches to assess the daily auspiciousness or inauspiciousness. Their individual connotations are as follows:

- Jian: Represents robust and flourishing energy. This day is deemed most auspicious—favorable for military campaigns, travel, inviting fortune, consulting influential figures, and offering counsel.

- Chu: Connotes the elimination of the old to welcome the new. It is an opportune day for changing attire, seeking medical remedies, dispelling malevolent influences, traveling, or celebrating weddings.

- Man: Implies abundance and completeness. It is suitable for inviting blessings, forming alliances, launching enterprises, or celebrating significant friendships.

- Ping: Denotes a state of neutrality—neither auspicious nor inauspicious.

- Ding: Suggests a state of inertia; a day marked by stillness that may hinder proactive endeavors, making it more suitable for planning rather than action.

- Zhi: Conveys steadfastness, perseverance, and moral rectitude, rendering it favorable for inviting blessings, performing rituals, seeking progeny, marrying, or formalizing agreements.

- Po: Indicates excessive rigidity that leads to collapse—detrimental to marital harmony, though it may be apt for medical treatments, examinations, or pursuits of scholarly success.

- Wei: Signifies danger. On such a day, activities such as mountain climbing or engaging in risky ventures should be avoided.

- Cheng: Connotes success, achievement, and fruitful outcomes. It is propitious for inviting blessings, advancing in education, opening a business, marrying, undergoing treatment, traveling, relocating, or commencing a new position.

- Shou: Implies harvest and collection, making it favorable for commercial endeavors, seeking fortune, real estate transactions, or wedding celebrations.

- Kai: Denotes openness and joy—advantageous for attracting wealth, seeking progeny, forging relationships, or pursuing employment opportunities.

- Bi: Suggests solidity and fortification. It is especially propitious for burials, symbolizing enduring prosperity and is also suitable for business ventures or assuming new roles.

Defining the “Four Wastes”

What are the “Four Wastes”? This term refers to days in each of the four seasons when the day’s elemental attribute clashes with that of the season. For example, spring is governed by Wood; however, days such as those corresponding to Gengshen and Xinyou—both associated with Metal—are deemed wasteful in spring, as Metal overcomes Wood. In summer, ruled by Fire, the days corresponding to Renzi and Guihai (which embody Water) are in discord with the season’s fiery nature, rendering them unfavorable. In autumn, when Metal predominates, days corresponding to Jiayin and Yimao (which are associated with Wood) engender a conflict. Likewise, in winter, characterized by Water, the days corresponding to Bingwu and Dingsi (linked with Fire) are considered inauspicious due to the inherent antagonism between Water and Fire.

Individuals whose Four Pillars (birth charts) contain these “waste” days are often thought to be frail and prone to illness, lacking perseverance and steadfast resolve. Their endeavors may commence with vigor only to peter out, and they may be more susceptible to accidents, injuries, or even entanglements in legal disputes, thereby experiencing considerable discord in life.