Tai Chi Liang Yi: Ancient Wisdom Behind Balance

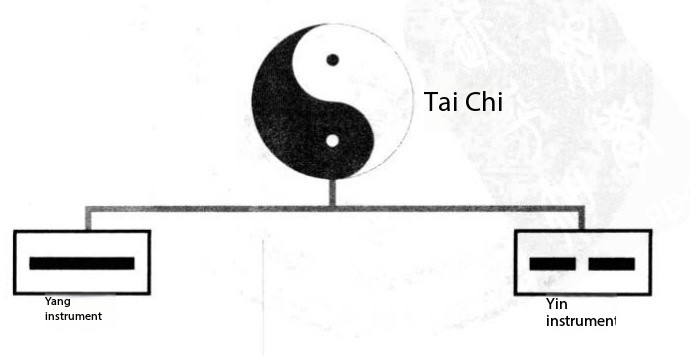

In ancient Chinese philosophy, “Liang Yi” (两仪) is a fundamental concept rooted in the study of the I Ching (Book of Changes). The term first appeared in The Commentary on the Appended Phrases (Xici Shang) of the I Ching, which states: “The Yi has the Supreme Ultimate (Tai Ji), and it produces the Two Modes (Liang Yi).” These Two Modes refer to the Yang Mode (Yang Yi) and the Yin Mode (Yin Yi).

While the concept of Yin and Yang is more commonly recognized in Western culture, there is a subtle but important distinction between Yin-Yang and Liang Yi. Yin and Yang primarily describe abstract concepts, while Liang Yi is often represented visually, making it more tangible in its depiction.

The Connection Between Liang Yi and Chinese Martial Arts

Liang Yi plays a significant role in traditional Chinese martial arts. According to early martial arts theories, Tai Ji(Supreme Ultimate) initially existed in an undivided state. It was something formless yet inherently present. The creation of Tai Chi forms, such as Tai Chi Chuan (Taijiquan), was guided by this principle. As Wang Zongyue, a revered Tai Chi theorist, explained:

“Tai Ji arises from Wu Ji (Limitless Void). It is the mechanism of motion and stillness and the mother of Yin and Yang. When in motion, it divides; when still, it unites.”

This statement encapsulates the theoretical foundation of Tai Chi Chuan, highlighting the interplay of opposites—motion and stillness—as the key to its practice.

Over time, Liang Yi became widely integrated into martial arts theory and techniques. For example, the legendary martial artist Sun Lutang described the interplay of movement and stillness in martial arts as the Liang Yi of Motion and Stillness:

“The body alternates between moving and being still—this is Liang Yi.”

Sun also extended the concept to Bagua Zhang (Eight Trigrams Palm), explaining the left and right circular movements as Liang Yi in action:

“Liang Yi represents the principle of expansion and contraction in a single flow of energy. Leftward rotation corresponds to Yang Yi, while rightward rotation corresponds to Yin Yi.”

Modern Interpretation for Martial Arts Enthusiasts

For those familiar with Tai Chi or other martial arts, the concept of Liang Yi can be understood as the dynamic relationship between opposites that fuels martial energy. Whether it’s the balance of tension and relaxation or the alternation between advancing and retreating, Liang Yi embodies the essence of harmony through contrast.

This philosophy extends beyond combat and into daily life, offering a lens to perceive the balance between opposites—work and rest, action and reflection, or even progress and patience. By understanding Liang Yi, we not only deepen our grasp of martial arts but also find a guide for achieving equilibrium in a chaotic world.

The Legend of the Cosmic Dancers

A long time ago, in a mystical land of ancient wisdom, there was a legend about two cosmic dancers, Yin and Yang. These dancers were the children of the Great Circle, known as Tai Ji, which symbolized the ultimate balance and potential of the universe. For eons, Yin and Yang danced in harmony, shaping the world with their fluid movements—Yin embodying stillness and introspection, Yang representing action and energy.

But as time went on, the Great Circle grew curious. “What if the dance became more intricate, more dynamic?” it mused. And thus, the Great Circle created two new dancers, the Liang Yi—the Movements of Yang (Yang Yi) and Yin (Yin Yi).

These new dancers brought a revolutionary twist to the cosmic choreography. Instead of abstract ideas, their movements took physical form, creating visible patterns that inspired the early sages. When Yang Yi moved, it was a powerful outward leap, like the sun rising boldly in the sky. Yin Yi, on the other hand, was a quiet inward spiral, like a peaceful moonlit night. Together, they showed how balance could be achieved through motion itself.

Enter the Warrior’s Path

One day, a young martial artist named Sun wandered into a forest where the cosmic dancers were said to perform. Sun had been training in the art of Tai Ji, but he was struggling to understand its true essence. “How can I fight without force?” he wondered.

As he sat under an ancient tree, the ground beneath him seemed to hum with energy. Suddenly, the dancers appeared—Yang Yi spinning to the left with fiery intensity, and Yin Yi gliding to the right with serene grace. Their movements created a natural flow, a perfect circle of energy.

“Watch and learn,” the dancers whispered.

Sun began to mimic their motions. He realized that every powerful outward strike had to be balanced by a quiet inward retreat. Every bold advance needed a calm recovery. The movements weren’t just random—they followed the rhythms of the universe, a never-ending cycle of expansion and contraction, action and rest.

The Birth of a New Style

Years later, Sun became a master of martial arts and shared the wisdom of the Liang Yi. He taught his students to see motion and stillness not as opposites but as partners in the same dance. When they practiced, he reminded them:

- “When you step forward aggressively, let it flow like Yang Yi’s outward leap.”

- “When you retreat, do it with Yin Yi’s quiet grace, ready to spring back when needed.”

He even adapted these principles to Bagua Zhang, teaching his students to walk in circles—turning left with Yang Yi’s energy and right with Yin Yi’s calm focus.

The Everyday Dance

For Sun’s students, Liang Yi wasn’t just about martial arts; it became a way of life. Whether plowing fields, writing poems, or resolving conflicts, they saw the world as a dance of motion and stillness, action and reflection.

And so, the legend of Liang Yi reminds us even today: Life is a constant interplay of opposites. By learning to embrace both the bold leap and the quiet spiral, we can move through life with balance, grace, and strength.