Why Did the Ancients Consider ‘Carrying Yin and Embracing Yang’ to Be the Key to Unlocking the Universe’s Secrets?”

The phrase “All things carry yin on their back and embrace yang in their arms; the interplay of these energies creates harmony,” originates from Laozi’s Tao Te Ching. It reflects the fundamental principles governing the existence and movement of all things in the universe. Laozi also stated: “Being and non-being give rise to each other; difficulty and ease complement each other; long and short contrast each other; high and low rely on each other; sound and silence harmonize; front and back follow one another.” This philosophy views opposites—such as existence and nonexistence, difficulty and ease, or sound and silence—not as isolated elements but as interconnected components of yin and yang. These relationships are eternal and interdependent. The practical application of this wisdom is particularly evident in the disciplines of Tai Chi and calligraphy, which we’ll explore further.

1. Tai Chi: The Dance of Yin and Yang

Tai Chi is deeply rooted in the concept that “the ultimate void gives rise to Tai Chi, and Tai Chi generates yin and yang.” Its principles align with the cosmic harmony of “aligning with the virtue of heaven and earth, and resonating with the brilliance of the sun and moon.” Every movement in Tai Chi reflects the interplay of opposites: motion and stillness, fullness and emptiness, hardness and softness, above and below, inner and outer, fast and slow. These contrasts embody the essence of “carrying yin and embracing yang.”

Central to Tai Chi philosophy are teachings like “motion generates yang, stillness generates yin; motion and stillness are rooted in one another” and “maintain a tranquil mind and upright posture, allowing the mind to guide the body.” These principles showcase the dynamic unity of yin and yang. Achieving harmony between these forces allows practitioners to transcend duality and grasp the “divine way.”

2. Calligraphy: The Art of Balance

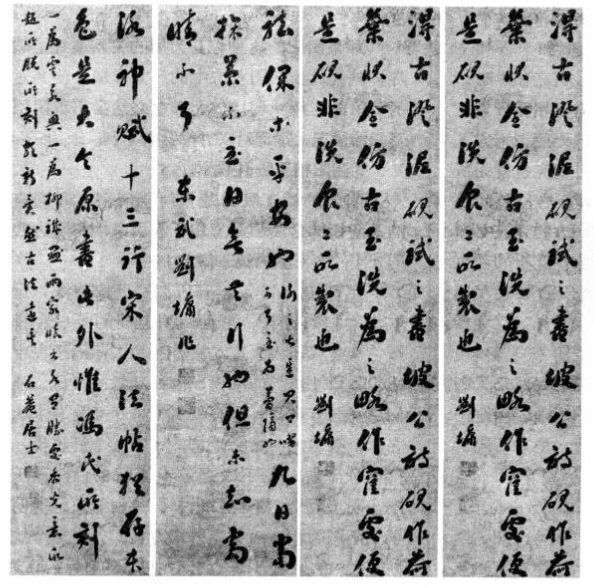

Calligraphy theory holds that “yin and yang are not two separate entities; the universe centers within me.” Through the interplay of black and white lines, calligraphy seeks to achieve the harmony of “carrying yin and embracing yang.” Techniques such as balancing angularity with smoothness, revealing and concealing strokes, and alternating between bold and delicate lines illustrate the dialectical unity of yin-yang harmony.

As Liu Xizai observed in Art Concepts, “Calligraphy must embody the energies of both yin and yang. Depth and restraint represent yin; boldness and grandeur represent yang.” Thus, the art of calligraphy demands the seamless integration of these dual energies.

In Jiang Baishi’s Continued Calligraphy Manual, he wrote: “Brushwork should not be overly thick, as excessive thickness leads to muddiness; nor should it be too thin, as thinness results in lifelessness. Avoid exposing too much of the brush tip, as it appears careless; but do not overly conceal the brush’s angles, as it lacks vigor. The top should not overshadow the bottom, nor the left dominate the right. Neither should there be too much weight in the front, leaving the back insubstantial.” These nuanced guidelines vividly reflect the dialectical relationship expressed in the phrase “the interplay of energies creates harmony.”

Bridging Cultures

For a Western audience, Tai Chi might be likened to a moving meditation that balances body and mind, much like yoga harmonizes breath and posture. Calligraphy, meanwhile, parallels the Western art of typography and design, where form and function converge to create beauty. Both practices remind us that balance is not about eliminating opposites but embracing their interdependence—a timeless lesson from the East that resonates universally.

The Dance of Balance: A Modern Tale of Harmony

It was a crisp autumn evening in New York City, and Amanda stood on the rooftop of her apartment, gazing at the sprawling skyline. Her mind buzzed with a decision she couldn’t seem to make—whether to stay in her high-paying corporate job or take a leap of faith and pursue her passion for dance.

Amanda’s life had become a tug-of-war between two opposing forces: security and freedom, logic and emotion. Every time she leaned toward one, the other would pull her back. Exhausted and feeling stuck, she sighed, “Why can’t I find balance?”

A Chance Encounter

The next morning, Amanda wandered into Central Park, hoping a walk would clear her head. As she turned a corner, she noticed a small crowd gathered around an elderly man performing Tai Chi. His movements were fluid, almost like a slow dance with the wind. Intrigued, Amanda joined the onlookers.

The man, sensing her interest, smiled and motioned for her to come closer. “Are you curious, young lady?” he asked with a thick accent and a twinkle in his eye.

“Yes,” Amanda admitted, “but I don’t know much about what you’re doing.”

“This is Tai Chi,” the man explained. “It is the dance of yin and yang, the harmony of opposites. Let me show you.”

He guided her through a series of movements. “In Tai Chi, when one part of the body moves, another remains still. When you push forward, you must also pull back. Motion and stillness, strength and softness—they are all connected. If you fight one, you will never find peace. But if you embrace both, you create balance.”

The Practice of Harmony

Amanda began attending the man’s morning Tai Chi sessions. At first, the slow movements frustrated her; she was used to the fast pace of her corporate life. But over time, she noticed a shift. The deliberate balance between movement and stillness calmed her restless mind.

She started applying the lessons of Tai Chi to her decision-making. One day, as she watched the man’s movements, she recalled a principle he had taught her: “Motion creates yang, stillness creates yin. They are two sides of the same coin.” She realized her choice wasn’t about abandoning one life for another; it was about blending them.

The Turning Point

Inspired, Amanda crafted a plan. She proposed a flexible schedule at work, allowing her to teach dance classes in the evenings. Her boss, impressed by her initiative, agreed. Amanda’s new routine gave her both the stability of her job and the freedom to pursue her passion.

One evening, after a successful dance class, Amanda lingered in the empty studio, staring at her reflection in the mirror. Her movements echoed the Tai Chi she had learned: a perfect balance of grace and power, stillness and motion.

The Unexpected Lesson

Months later, Amanda decided to thank the man who had introduced her to Tai Chi. But when she returned to Central Park, he was gone. In his place, she found a note pinned to a tree.

It read:

“Life is a dance of yin and yang. Embrace both, and you will find harmony.

— Laozi”

Amanda smiled, feeling a warmth she couldn’t explain. She had finally found the balance she’d been searching for—not just in her movements but in her life.

The Calligraphy of Life

Amanda’s journey didn’t end there. Inspired by her experience, she took up calligraphy, finding joy in the contrast of bold and delicate strokes. Each letter she crafted was a reminder that opposites aren’t enemies—they’re partners in the art of living.

Her story became a metaphor for many: the balance between work and play, ambition and rest, strength and vulnerability. Amanda began sharing her journey online, connecting with others who were also searching for harmony in their chaotic lives.

The Emotional Climax

Years later, Amanda stood on stage at a conference, sharing her story with thousands. As she demonstrated a simple Tai Chi movement, she said, “Harmony isn’t about choosing one path or the other. It’s about embracing the interplay of opposites. That’s the dance of life.”

The crowd erupted into applause, many wiping tears from their eyes. Amanda felt a deep sense of fulfillment—she had not only found her own balance but had helped others discover theirs.

Closing Reflection

In the end, Amanda realized that life is much like calligraphy or Tai Chi. It’s not about perfecting every stroke or movement but about finding the rhythm where opposites meet. And in that rhythm lies the true art of harmony.